on the road to ulter nation

Quote featured on the back cover of Scott 4 by Scott Walker.

The journey detailed in this essay is a journey I’ve endeavored to capture sonically on an album called ulter nation (now available on CD and digital download). It is a journey that sometimes flows from track to track—and other times, jolts from one idea to another. Like a gesture that hesitates to decide its own course, for want of constantly considering the alternatives. It’s sometimes polished, and sometimes messy; sometimes big (verging on claustrophobic), and sometimes small and questioning. Over the past months, I’ve often doubted whether it’s worth releasing it at all (who’s going to listen, anyway?): the decision I’ve made to do so is grounded in a belief that every journey deserves to be documented—however meandering or insignificant it might seem to the individual who traversed it. Write what you know, as the old saying goes.

Official music video for album opener, “Eclipse”—featuring footage from the films of Michelangelo Antonioni.

Part I: Travels abroad

“…and I ride and I ride…”

As far back as I can recall, film has been a part of my life. I grew up in a three-story apartment building in Northern Italy: my parents were stationed there as missionaries, and the entire structure had been designated a “hospitality house” for the soldiers of a nearby Army base. The edifice was a square, stuccoed ordeal, and there was a large magnolia tree out front that would yield big white blossoms during the Mediterranean summer. I remember very little about the Army base itself—which we were only allowed to visit on civilian permit—other than the American movie theater at the heart of it, and the Italian cinema/video store combo across the street from its gates. These would be the sources of my earliest obsession.

I can vividly remember roaming the tall, stately rows of VHS tapes, lined up throughout the Italian video store—which was, in fact, functioning as an outlet for American soldiers who wanted something beyond the range of the smaller rental store on-base. This meant most of the videos were in the NTSC format; which, in turn, meant we could watch them on our American-made VCR. I can almost (but not quite) smell the nicotine-stained, styrofoam-packed video sleeves lining the shelves: the faded corners around the cover artwork of each title; the wall of artlessly catalogued cassettes behind the register. The stern but warm face of the middle-aged matron who ruled over the place with a disinterested (yet well-versed) sense of practicality; the printed ledger, which contained an alphabetized—and somehow always up-to-date—account of every title in-stock, in case a customer had a specific request. Oddly enough, I remember much less about its on-base counterpart: this could have been due to our being civilian visitors, and only being allowed to visit the American store at limited times. It could also have been that the Italian store was far more compelling, with its combination of cult and mainstream English-speaking fare, and the more exotic-(shall we say)-looking Italian films on a wall close to the register.

The two movie theaters in town held my intrigue in equal measure—and for similar reasons: whereas the movie theater on base could be relied upon to always have the latest American blockbuster, the Italian theater across the street primarily exhibited movies my parents wouldn’t be overheard talking about in public. But this became an amusing little routine for me: about once a year, mom and dad would find an Italian film showing that seemed to be child-appropriate; the four of us—my parents, myself, and my older brother—would venture out and, inevitably, one of them wound up scrambling to cover our eyes during a scene of spontaneous nudity (usually occurring in the second act, when the attention starts to lag due to the notoriously bad post-syncing). I can’t say we visited the military-operated theater with any degree of regularity; our finances were understandably limited. Perhaps it was my unfulfilled longing to know more about every mysterious movie poster that provoked this cinematic fascination which overtook me in later years.

Outside of these consumption outlets, film played a role in our family image development: my parents always seemed to have a camera on-hand, and they’ve kept a fairly comprehensive record of the 11 years we spent overseas. When our family was gifted a direct-to-VHS video camera, we started recording significant (and sometimes insignificant) events as little home movies. I recall one of these movies perfectly capturing my anxiety as a 7-year old on Christmas morning: my parents, good Christians that they are, made certain myself and my brother both sat through a retelling of the Nativity prior to any worldly gift exchanging. Part of me grew irritated by the monotony of the story (it always ended with the virgin having a baby—which likely triggered my later interest in surrealism); another part of me learned to appreciate the value of tradition—the accrued significance an event can obtain by virtue of its repetition. Both parts of me must have been fully functioning on this particular Christmas morning, as I hyper-actively jumped from the couch to the floor, to the stockings on the mantel, back to the couch, and back around in a (sort of) circle. While watching the video of this event some time later—and fast-forwarding through the Nativity section—we stumbled upon a happy accident: as the tape ran through the VCR in fast-motion, the action of my hyperactive body leaping around the living room revealed a rhythm. What at regular speed just seemed to be restless wandering became a sort of dance, when played at a different rate: like one continuous gesture, weaving throughout a designated space.

“…I ride through the city’s backsides…”

There’s this scene in Antonioni’s 1975 feature film, The Passenger, in which our protagonist (played by Jack Nicholson) lies dying in a hotel bed—fulfilling a predestination, set in motion by the death of the man whose identity he adopted at the movie’s beginning. The camera gaze drifts slowly outside the room, through the bars of a window overlooking the courtyard of some desert hotel. A man sits still in a chair against a wall. Maria Schneider wanders restlessly around the courtyard. A car drives slowly through the scenery. It’s one of the longest continuous shots I can think of, and when examined as a microcosm within the film’s narrative, it represents a sort of gestural solution to a fairly Quixotic, meandering plot.

Still from Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger © 1975, Sony Picture Classics

A series of shots at the end of his earlier film, L’Eclisse, betrays a similar strategy: delivering on the promise of its title, the gesture inherent to this series of still lifes rather passively brings to a close the film’s narrative (which, to be fair, has no real need for closure). The same could be said for a number of his other films, including my personal favorite—Identification of a Woman—which concludes with the lead actor opening a window to project his imagined sci-fi screenplay idea (which, in turn, projects a story narrated by Monica Vitti in Red Desert) into an open sky of improbable colors. I suppose another viewer might interpret these as cop-out endings, but they don’t come across to me as such. The gesture of each ending seems to catapault the viewer back to his own reality—which represents just one out of a number of possible gestures.

“…I see the stars come out in the sky…”

In 1999, my family packed up the few belongings in our expansive Italian house and moved back to the United States. As the Y2k scare swelled to its inevitable (and underwhelming) conclusion, we were settling into a rented home in the middle of an identikit suburban neighborhood. I remember the television coverage on New Year’s Eve—sitting on the carpeted floor of the living room, wondering if this move to a different country could also become a move to the end of the world. Some people must have been disappointed by the outcome, since the scenario was reprised (somewhat less effectively) the following New Year’s, with a scare surrounding the ’00 turning to a ’01. Who knew basic algebra could be this frightening?

Still taken from Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation © 2003, Focus Features

Official music video for “Into the Night (pt. I),” celebrating a range of films which left a lasting mark on your humble narrator.

The neighborhood we moved into was made up of block after block of indistinguishable one-stories; you could (and I did) ride a bike through this maze for hours, racking your brain to find your way back to the street you lived on. Directly across a heavily trafficked 4-lane road on the edge of our neighborhood, there was an expansive strip mall—which housed a used music and movies store, but more impressively (and all the way towards the back of the labyrinthine lot) a proper multiplex. While the distance was a little demanding on foot, it turned out to be the perfect range for a bicycle. This enabled your humble narrator to pick up his consumption of new movie releases at a significant rate—within budgetary restrictions, of course. I remember seeing features as diverse as Signs; Lost in Translation; Kill Bill; Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. All in rapid succession. It must have been this exposure to another side of American cinema that opened an alternate dimension for me—one to rival the microcosm of that Italian video store.

It was this exposure to a “rebirth” of independent American cinema that inspired me to return to my roots: to find out about those movies I never get to see while I was growing up. My mother had found work as a public librarian, and this enabled me to dig into a variety of books on the history of cinema, as well as digging into older films (on VHS and the new DVD format) from all around the world. The Italian film selection intrigued, but also confused me, since it seemed to represent an entirely different side of Italian cinema than the side I saw while growing up overseas. Not only were the films mostly older titles—films by DeSica, Visconti, Rosselini—but they seemed to represent a somewhat artisinal curation of a culture I found to be far more eclectic. For instance, none of the titles I checked out from the library synced with memories of dumb comedies starring Fantozzi and Roberto Benigni; none of these “classic” Italian films—though they were all pretty good—really matched the indigenous cinema I had once known and loved.1

Still taken from Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits © 1965, Studio Canal Films

So I started to branch out, and I found the works of Bertolucci and Pasolini; films by Antonioni, Fellini, Leone, and Tornatore. I found films that were as far removed from the tripe I saw on Italian television as possible, yet just within range of the concerns I faced as a gay teenager. In Bertolucci, I found desperate, sensual beauty; in Pasolini, desparate anarchy. In Antonioni, it was the so-called “alienating” gaze that grabbed my attention (and subsequently found its way into many of the songs on this new album). In the films of Fellini, those wonderful outrages of the imagination—soaring on self-reflexive wings through fragments of deconstructed memory. Leone, on the other hand, was more of a magic realist: his majestic pipe dream, Once Upon a Time in America, may well be the quintessential cinematic rumination on memory and loss. And Giuseppe Tornatore brought me full circle, with his desperate love of life saturated in every film cell for The Legend of 1900 (a film I spent years searching for, having nothing to go on but my vague recollection of the teaser trailer shown on Italian television). I do believe a love of life is the defining characteristic of all the finest movies; it’s this act of love that inspires the viewer to become a better version of himself, thereby fulfilling the definition put forth by Roger Ebert—“a machine that generates empathy.” Just as the writers of Cahiers du Cinéma had incited a revolution (of sorts) through the act of championing the very lifeblood of cinema, my discovery of passionate Italian film-making incited an unquenchable thirst for more of the same.

One of the first stops along the tracks of this bullet train through world cinema was the land of surrealism.

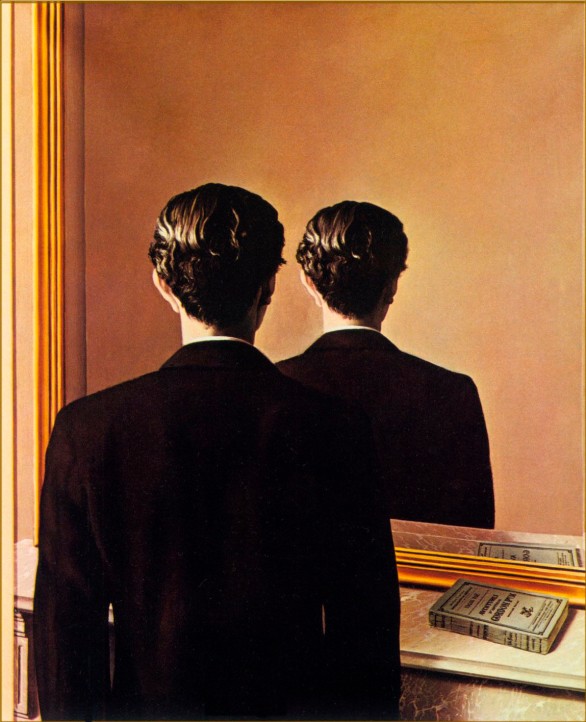

René Magritte’s portrait of Edward James (1937)

“…yeah, the bright and hollow sky…”

Surrealism seems to get a bad rap from most art historians. I think this is largely to do with a perceived constriction of art that serves solely to attack bourgeois values; for the record, I’ve never bought this open/shut interpretation. Having admired the strange and enchanting films of Luis Buñuel for many years now, I’ve recognized a more consistent thread coursing this art movement to be a study in gestures. If we rewind all the way back to Magritte’s painting of a man (Edward James) reflecting the back of his head in a mirror (while facing the other way), we’ll find that the artist has taken a common subject and rendered it fascinating with a hidden gesture. At the most basic level, the image functions as an optical illusion; upon further scrutiny, it captivates with the perpetual (and unfulfilled) suggestion of some inscrutable movement.

Fast-forward to the improvisatory, episodic trajectories of Buñuel’s The Milky Way and The Phantom of Liberty, and you have this play of movement and gestures taken to the remotest extremes of unpredictability. More-so than satirizing a social class, these works seem (at least to me) to be studying the chance element inherent to the formation of social norms. When seen as a series of incomprehensible—yet, somehow, logical—gestures, we are granted the realization that alternate possibilities will always lie in waiting, just beyond the confines of our actualized movements. We are granted the realization of life as one long series of gestures: one long movement, which could have been any number of ulterior movements.

Still taken from Luis Buñuel’s The Milky Way © 1969, Studio Canal Films

These works by “formal” surrealists2 segued neatly into my exploration of the dream-drenched boudoirs in the films of David Lynch (it wasn’t until many years later that I learned of the association his films held to the surrealist art movement). There was also the wide and varied work of Robert Altman, which—while not “surrealist” in any proper sense of the word—was energized by improvisation and obliqueness. 3 Women, in particular, seemed to share just as much with the works of surrealists as it did with the works of Ingmar Bergman. It’s one of (if not the) best-captured dreams on film, as far as I’m aware.

Panoramic still taken from Robert Altman’s 3 Women © 1977, Lion’s Gate Films

It seems to be dreams that most accurately capture the disorientation I’ve sometimes felt, straddling two cultures of origin. It was in dreams that I revisited the hallways and courtyards of the Italian schools I once attended; in dreams that I sometimes still catch glimpses of the life we left behind. Dreams have kept my fading memories of childhood alive, but they also tend to mutate these memories into increasingly fragmented images. The geography of my youth was one I traversed with little sense of orientation as a child: it’s now somewhat difficult for me to map these memories in any concrete order or sequence.

Maybe it’s this disorientation of recollection that fed my love of American road movies: Kubrick’s Lolita; Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider; Five Easy Pieces, Deadhead Miles, and Two-Lane Blacktop; Kalifornia, Thelma & Louise, Wild at Heart, and True Romance. Terrence Malick’s Badlands and Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho… They all channeled—in one way or another—this restless wandering of the soul, often through unknown towns and their roadside motels. The road movie may in fact be the perfect metaphor for the restless soul: it offers a literal depiction of the soul’s endless wandering; it establishes a tangible geography for an intangible journey. Just recently I saw Wim Wenders’ Kings of the Road for the first time, and it struck me as a flawless melding of the existential and the functional elements inherent to the genre (that infamous scene on the beach just about sums it up). It deserves to be crowned the king of all road movies.

Still taken from Wim Wender’s Kings of the Road © 1976, Axiom Films; renewed © 2016, Criterion Collection

“…you know it looks so good tonight…”

The latest stop on my journey through cinema has been the spellbinding land of melodrama. This includes everything from the expatriate works of Douglas Sirk, to the no-less-brightly-colored—and equally perverse—domestic dramas of Almodóvar; the filmed plays of Tennessee Williams, and the brutal genre/chamber pieces of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. The lavish love letters of Wong Kar-Wai, and the cream of the day/night-time soap opera crop: Peyton Place, Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, Twin Peaks… The overly deliberated, deliciously exaggerated gestures of all those existentially bothered characters.

There’s this wonderful string of episodes in the second season of Mary Hartman‘s nightly run, during which Louise Lasser finds herself corresponding with Gore Vidal from the confines of a mental health facility—providing the world-renowned satirist with insight into the trials and tribulations of a sexually repressed housewife. What at first appears as a borderline-ludicrous juxtaposition of personalities, winds up a mirror image of sorts: two people sharing this tremendous amount of perception regarding (their respective) sources of societal misery, but only one of them capable of tapping into repressed desire. The irony of this dynamic, of course, is that the hetero-normative individual in this scenario is the one most incapable of finding happiness within the confines of social structures (thereby affirming Yoko Ono’s eyebrow-raising claim3).

Still taken from an episode of Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman © 1976, Sony Pictures and Shout! Home Entertainment

I could not have prepared myself for the outcome of the recent United States Presidential election, regardless of how hard I might have tried. As this country veers off into an uncertain future, I believe it will be noted by historians that the final straw before the breaking of the camel’s proverbial back was the threat of a woman achieving power. It is a given that sexism will not allow itself to be resolved any time soon, and it is this oppression that makes melodrama a study of such on-going relevance: it’s a genre centered around the awareness that society sides with one “type,” often at the sacrifice of another. Emerging forces of opposition are allowed to be studied with complexity and nuance in melodrama, and when done successfully, this creates the ultimate machine for empathy. This fosters the ability to recognize one’s “other” for who he/she/they really are, and we can then begin to comprehend where the scales are tipped. This heightened awareness is the first step towards developing an altered and improved model of the status quo.

“…I stay under glass…”

There is a dynamic that occurs when an organism responds to its surroundings: I refer to it as the “politics of space,” though I’m certain there’s a more scientific term in use elsewhere. The Canada goose, as we know, flies south in the winter to escape the frost; the lizard seeks sunlight to absorb the heat its body fails to generate adequately. Similarly, people respond to space in terms of opposition and assimilation. Living in Italy, I developed a curious obsession with the grandiosity of American culture—it being in such direct opposition to the scale of Italian geography—but for reasons beyond mere opposition: in this grandiosity of physical space (the Rocky Mountains; the deserts of Arizona and New Mexico; the vast tundras of Alaska and Canada) there can be found a reflection of the spiritual grandiosity Italians are well-known for.

The narrow geography of Italy has forced many citizens to establish tight-knit communities. Combined with the (once-stringent) policy put forth by the Vatican on birth control, this proximity of space in more industrialized cities made it so that—at the time I was there—families of 10 or more resided communally in two-bedroom flats. It was not unusual for us to visit our neighbors and find the husband sitting on their living room couch, wearing only his underwear and a tattered shirt: the living room often doubled as a bedroom/changing area, and some of the boundaries many “westerners” are accustomed to were frequently blurred.

As a general rule, upon entering an Italian household, life will light itself up. The Italians I met from Southern Italy, in particular, tended to move with grand, welcoming gestures; they were good-humored, hospitable, and down-to-earth. But all Italians (that I recall meeting, at least) seemed to share this grandness of spirit, which endeared you to people upon your very first meeting them. Genuineness among people felt instinctual: whereas North America (as we know it) was initially colonized in the vein of forming a new identity, Italians have retained a fairly confident sense of national identity for a while now. This sense was so confident, of course, that it once swung to the extreme of fascism—but this part of Italian history was seldom brought to my attention (and when it was, it rarely resonated within my youthful, ahistorical thought process).

Another thing about Italians (culturally speaking): very little seems to be done in a spirit of irony. Humor often inclines itself towards the wicked variety, but it rarely sinks to a level of actual cruelty (some lightweight debasement, perhaps), and it always feels close to home. Perhaps taking a path whereby few subjects ever require skating around, Europeans have side-stepped some of the common traps we Americans appear to fall into; specifically, traps involving the formation of social taboos that, when confronted by youth, frequently turn into vindictive norms. These traps can provoke a susceptible individual’s instinctive rejection of their environment, in lieu of confrontation or assimilation. Europeans, on the other hand, have been forced to confront their environment time and again; their consistency and solidarity (despite numerous wars and territorial squabbles) is viewed as remarkable by Americans, who’ve experienced something akin to schizophrenia between the disparate and far-removed parts of our country. Perhaps it’s this increased sense of national identity that enables Europeans to maintain the cultural upper hand.

Nonetheless, despite a heritage of great art and historic architecture—the Vatican; the Coliseum; the museums of Venice—the cultural components I connected with most immediately during my residency overseas were of a much more lighthearted nature. The Smurfs (translated as I Puffi) were a daily feature in our household after school, along with this great Japanimé series dubbed in Italian, Lupin III. There was also a sort of Disney knock-off cartoon serial (paper) that we used to pick up from the train station depot, whenever we went on a trip through the countryside.

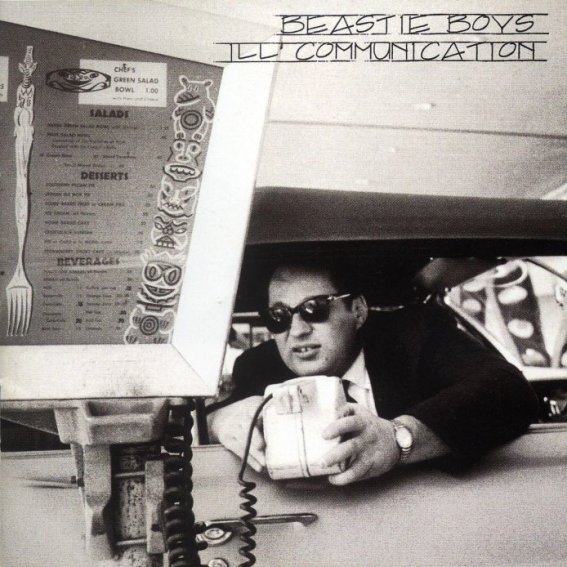

Still taken from the Mark Romanek-directed music video for “Bedtime Stories” (1995), one of many memorable Madonna moments from her MTV heyday

(Italian) MTV introduced me to a number of significant cultural icons, including Björk, Madonna, and David Bowie. There were also several Italian pop stars in heavy rotation—namely, Eros Ramazzotti and Jovanotti—and of course, the wonders of Ricky Martin’s hot candlewax threshold. Euro-pop is a real thing, make no mistake: the regrettable Swedish export, Ace of Base, made for ubiquitous listening in Italian supermarkets. There was also a strong affinity for UK-exported boy/girl bands, like Boyzone and The Spice Girls. But the CDs I found myself drawn to whenever we shopped at a retailer that carried music (which was a surprisingly large percentage of retailers, honestly) tended to be of a somewhat different nature: I vividly recall the covers of those early Massive Attack records (the name sounded so dangerous and alluring), as well as the Fat of the Land album by Prodigy. Then there was the first album by Tori Amos, with that startlingly graphic painting on the back cover—and, at the other end of the spectrum, the sinister-looking passenger on the front of Ill Communication. These were to be my forbidden fruit: if I found myself in any position to sneak a bite, it was a treasured moment.

Album artwork for Ill Communication by the Beastie Boys © 1994, EMI

Looking back, I never really questioned the appeal of the “girl power” supernova, or Euro-trash one-hit wonders like Aqua: it made perfect sense to me that young people should find freedom in sounds that seemed bigger-than-life. Bold gestures of generic convention offered an oasis for young girls (and boys) trapped in shared bedrooms with multiple siblings. Much like Titanic when it was unleashed upon an unsuspecting box office, “Wannabe” and “Barbie Girl” swept my schoolmates away from the humdrum routines of family living. This self-generating machine of feminist chic was essentially a hybrid of the same sensibilities that once before produced the Electric Company and Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret (the polymorphously perverse sex ed. component of all this teenybopper fluff was especially confounding and alluring for boys, as I recall; they were often more likely to have memorized lyrics and choreography, now that I think back on it…)

Big music is significant, when living in a relatively small land. Big music implies big space, which implies big gestures. One of the defining features of Euro-pop, from this writer’s point of view, is the broadness of its gestures: lyrics tend to be generic and universal, and production values lean towards the indulgent and the simplistic. Building upon the tradition of disco, and the more vacuous end of the New Wave spectrum, ’90s Euro-pop/club music and feather-weight, caucasian-appropriated R&B represented a dead end to cultural hedonism. These beyond-MOR incarnations of pop brought those past undertones of fascism and segregation (undertones which had only lain slightly more dormant in the melting pots of disco and ’80s cross-culturation) into full relief. As soon as the ’90s sealed the 20th century in a veneer of artifice, there was little one could do to escape the capitalization of cultural integration (and on-going cultural appropriation). Once the recording executives realized there was a fortune to be made in petri-dish-curated line-ups, many execs appeared to (almost overnight) master the craft of mixing and matching specific personality “types” with the intent of achieving a broad, cross-sectional audience demographic. Through sheer chance or calculated precision, the “boy/girl band gurus” managed to instigate one superficially diverse overnight sensation after another.

Backstreet Boys. *Nsync. The Spice Girls. All Saints. Boys II Men. While young people latched onto the loud, compressed dance sounds of these automatonic groups, most adults recognized this as the end of the line for major recording studios (not to mention, the end of the line for proper A&R). Much like the “high concept” feature films, which appeared to drain the box office of all ingenuity and subversiveness during the ’80s, the efforts of different major labels to create self-prophesied hits drove the independent music scene further and further out of the woods and (eventually) into its own collective. The consumer who once gave unknown artists a chance by virtue of their being on a major (and therefore trustworthy) label, had now evolved into a consumer who sought out boutique labels, typically harboring counter-cultural connotations. The majors would have to settle for the likes of Adele and Taylor Swift, from here on out.

“…I look through my window so bright…”

Upon arriving in the United States, I was confronted with my nation of origin for the first time. I was barely one year young when my family flew to Italy for their 11-year term of civil service, and I had no notion of what to expect upon our return to the homeland (which, to me, was a totally foreign country). My parents had raised me speaking English; my schoolteachers had raised me speaking Italian. Torn between two tongues, I started to reflect upon the chance nature of cultural development: the notion that there are countless histories being written around the globe every day, but only a handful of these histories actually make it to the textbooks handed out in schools. The notion that every story involves a process of selection and omission—and that, oftentimes, it’s the omissions that define a story’s arc. I started to realize the significance of perspective; the importance of having a point of view, as well as the time and discipline needed to develop a well-rounded viewpoint.

Still taken from the music video for “Eclipse” © 2016, DirtyCleanMusik

I went to three different schools (one Middle, two Highs) before graduating, and wherever I went, I seemed to be flummoxed by the possibility of an alternative. I struggled to relate to others in my class—not because I didn’t like them or didn’t enjoy their company, but because my curiosity to find out how the other half lived kept me in a state of intellectual restlessness. I received fairly good marks up through my Junior year, at which time I surrendered my will to try harder than absolutely necessary and wound up graduating by the skin of my teeth (thanks, mom).

Post-graduation, I tended to wander from one social circle to another. This rarely rose to the level of more-than-superficial friendship, though I’m fortunate to still have some friends from this time—and less fortunate to have missed out on lasting friendships with others. I initially went to college upon my parents’ convincing, which led to my (still current) involvement with the social work profession. In a way, it’s the perfect field for a person with my particular intellectual inclinations: I meet a new mind every day—or thereabouts—but the treatment process is structured in a way that protects these meetings from the nagging threat of interminability.

Today, I feel very fortunate to have had the experience of living in a different country: it’s something I wish every person on this planet could do at some point (though I understand the logistics of this happening are tricky, to say the least). I can only speak from personal experience, but I believe that acculturation has strengthened my stability of perspective. My former experiences have instigated an on-going (and, at times, hyper-active) drive to develop and implement empathy, whenever possible. And throughout my 30 years of existence, it is empathy that I’ve found to be the greatest equalizer. It is empathy that truly binds individuals to one another, above and beyond the forced constraints of social norms—and it’s empathy that protects us from the hazards of carelessness.

Still taken from Fassbinder’s World on a Wire © 1973, Criterion Collection

There is a somewhat discernible decrease in understanding among individuals living through the digital age. As information becomes more and more readily available (quite literally, always at our fingertips), the value placed on comprehension and empathy seems to border on irrelevance now. It can be difficult for those who develop an appetite for sincerely empathic interaction to find a niche in internet chat rooms, but equally challenging to stumble upon opportunities for natural mingling in-person. As explored in the themes of Fassbinder’s Welt Am Draht, we’re often confronted by the awareness that we experience a level of dissonance between our perception and our reality, whenever we engage in digital communication; we’re having to identify our reality through filters and second-hand sources. It is safe to say, we are often reading the commentary before the text.

We are constantly responding to the stimuli of our environment—and everyone confronts the threat of overwhelming external stimulus. Everyone longs for an alternative to the negative situations in their lives, and everyone seeks the stability of home and familiarity. These are the things we share: the things that keep us together (“while the war’s going on”4).

Official music video for “Into the Night (pt. II)”—a continuation of the cinematic themes explored in its counterpart.

Pt. II: Homeland

“…over the city’s a rip in the sky…”

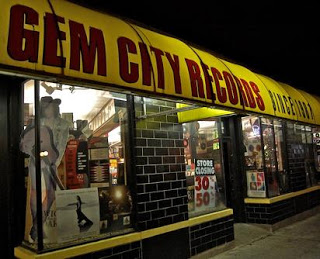

Storefront of Gem City Records, located in Dayton, Ohio (1987-2008). The space is currently under new management, operating as a storefront for Omega Music.

American culture in the late ’90s and early ’00s seemed to reject the grandiosity that came so naturally to it in years prior. Following the death of Kurt Cobain, and that burst of one too many punk-pop and alt. rock bands, the White Stripes took hold of many listeners who were thirsty for a return to something simpler. I recall visiting an independent American record store for the first time in the early aughts: it was nothing like the corporate-owned music stores in Italian malls, or the quasi-corporate used media store in the strip mall across from our suburban neighborhood. Dayton’s Gem City Records was something different and confounding to me: most of the new releases on display represented “smaller” artists, but the overall impact was just as expansive as that of a Virgin Records. I wandered those aisles for hours—much as I had wandered the aisles of that Italian video store—and tried to learn about as many of these artists as I could. I eventually hooked up with the clerk at this record store (we’re together to this day), but that’s a story all its own.

The year was 2003. With big music on the skids, a new folk revival was on the rise. I remember walking into the above-mentioned record store, asking for the latest studio album by Placebo on its release date: the knowledgeable clerk was aware of the release, but indicated they hadn’t ordered any copies for the store (they could place a special order, if I was interested). I was taken aback for a moment, because Placebo were bigger than Jesus in the Italian cool kids scene. They were just big enough to achieve “household” status, but small enough to retain some street cred—to not risk ready commodification at the hands of aggressive advertisers.

Another band of comparable cool in Europe, Garbage, seemed to be readily dismissed by most hip American music consumers, as well. I began to ponder what it was about these bands—bands that received steady radio-play and widespread appreciation in Italy—that didn’t resonate as easily with the average midwestern listener (after all, Garbage were based out of Wisconsin, with only their lead singer being of European origin). It came as a surprise to me that these bands were being read within the narrow parameters of “goth” music, and then subsequently dismissed under the guise of this lamentable term. It seemed, to me, a little lazy (not unlike those limiting interpretations imposed upon surrealism and disco).

In retrospect—and with both the aforementioned bands going strong in their respective endeavors5—the disconnect in question appears to stem, in part, from a politics of space. I realize that a component of the appeal these bands (and others: INXS; Eurythmics; New Order) held for European ears was the projection of a bigger-than-life quality. While the singers of these bands might have been shy (ahem, Bernard Sumner), their output rarely belied shyness (please see “Touched By the Hand of God”). Their output reflected a sort of longing for grandiosity: more specifically, a longing for a grandness that exceeded the confines of their origins. In Manchester, there was a need for the open/closed spaces created by the songs of Joy Division—and, later, for the dancefloor anthems of New Order. In the wake of Conny Plank and that great rebirth of German music, there was a place for the more grounded theatrics of Annie Lennox and Eurythmics. In the open landscape of the Australian outback, there was a longing to be packed shoulder-to-shoulder in an arena for the power-pop of INXS (or, on the flip-side of the pop music spectrum, the noisy barroom brawls of The Birthday Party—another export that never quite caught on among U.S. listeners).

Of course, thanks to the advance of globalism, one is now bound to find music of all sorts, in all corners of the world. But one is still bound to find trends and listening habits; genres that command critical and popular appeal in some pockets, but fail to connect with a larger audience in others. In my hometown of Dayton, for instance, there is an active local music scene: a new band or solo act seems to be popping up on Facebook and BandCamp just about every day. As in most small-city scenes, however, the range of genre and songwriting style tends to fall within a given section on the spectrum of possible musics. The spirit of Bob Pollard’s Guided by Voices—as well as the incredibly talented Deal sisters—seems to hover over the landscape of this music scene, and many interesting things have come (and continue coming) out of this influence.

The Breeders, achieving international recognition with The Last Splash

It’s interesting to note, however, that the Deals’ 4AD signing of The Breeders fell apart once they achieved bigger-than-life status: an epic achievement of grandeur, their second LP (The Last Splash) carried with it big venues, big expectations, and big parties; they ultimately retreated back to the smaller comfort of their hometown (though two more Breeders records emerged in later years). Pollard also struck it fairly big, signing with TVT Records and working with Ric Ocasek in 1999; he quickly determined the record industry would not be able to keep up with his output, and subsequently returned to the boutique circuit. It is fairly safe to assume he was correct in this assessment—and he’s had the last laugh by proving himself to be one of the most prolific songwriters in the midwest, if not the world.

I admire the loyalty so many of these individuals hold to the proxemics of their hometown: I find it inspiring, meeting people so dedicated to an established tradition of music-making. I must admit, I’ve still retained an unapologetic affinity for the over-the-top power chords of Placebo and Garbage (and INXS, and New Order, and Queen)—which must seem laughable to so many musicians who find this approach indulgent and “show-off-y.” When you live in the land of Big Macs and Cadillacs, but your local economy is sludging along at a snail’s pace, there’s often this urge to retaliate against the popular and the mainstream—to carve out an idiosyncratic niche for oneself, and to find solace in the smallness of one’s existence. The question I’ve asked myself (and the question I continue to ponder) is: can’t I have both?6

The ulter nation album teaser, featuring album track “Stairs.”

“…and everything looks good tonight…”

I’ve taken music lessons from two very different instructors over the years. My first experience with piano lessons began around age 6, after my parents took note of a habit I’d developed of drifting towards the instrument whenever we visited friends or family who had one on display in their living room. My first piano instructor taught lessons out of his apartment, which occupied an entire floor in a hauntingly beautiful pre-war building farther uptown from us. I recall the wide, well-worn stone staircase my mother and I climbed on a weekly basis to get to this apartment: whenever I re-watch Identification of a Woman—specifically, the opening credits sequence with Tomas Milian returning to his apartment, and that scene near the end where he locates the woman in question from the top of a spiral staircase—I think of those stairs.

Still taken from Identification of a Woman (1982) © 1982, Criterion Collection

My instructor, Alberto, was a traditionalist through and through. An impeccable player of the highest musical pedigree, Alberto held all his students to a comparably high standard: if he recognized that I had slacked in my practicing, he brought out a little switch and (gently) snapped it against my fingers whenever I hit the wrong note. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t develop a somewhat masochistic appreciation for the switch: why was it that playing the wrong notes felt so right to me; why was it that the punishment only seemed to validate my inclination towards coloring outside the lines?

When we moved back to the U.S., my mom started searching for piano teachers of a comparable caliber. When she stumbled upon a bearded beatnik fellow named Jeff, who walked with slow, graceful movements and played the piano with seemingly effortless virtuosity, she made the wise decision to sign me up for a weekly Thursday session in his studio. Lessons with Jeff could not possibly have been any more different from those traditional Italian lessons: for starters, the first 10 minutes rarely entailed any playing or music-reading at all. As soon as Jeff realized I was a fledgling movie buff, he quickly opened up about his own cinematic obsessions; before long, he had successfully turned me on to a number of memorably affecting American films: King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun; Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man; Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks; Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller. I started discovering a side of the American western that I never imagined could have existed; some books referred to it as the “anti-western,” but we recognized it as the “honest western.” Whereas most of the films starring John Wayne as “the Duke” tended to glamorize acts of genocide and homicide—while minimizing the horrors of ethnic cleansing, and the struggles inherent to frontier living—these westerns captured the American dream in all its strange, violent, disorganized power. Jeff broadened my geography of classic American film, and from here on out, talk revolving around recently-discovered movies became a staple of our weekly session time (on occasion, this would actually consume the majority of our time).

Jeff was (and remains) a firm believer in recognizing the individual intent of a given student. If I had come to his sessions saying I wanted to play Carnegie Hall, I’ve no doubt he would have played drill sergeant and enforced a strict rehearsal regimen in order to achieve marked progress towards that end; if I had come asking to be trained in different jazz stylings, he would have asked “where do you want to start?” But I asked for something more elemental. I asked to learn simply about chord structure, song structure, and arrangement—subjects of seeming irrelevance with my former instructor, a passionate and dedicated classicist whose teaching centered around reading and replication. I now wanted to understand what makes a song work, beyond the dots and dashes printed on sheet music (which, truth be told, I’ve never been even remotely proficient at deciphering).

The contrapuntal mastery of Glenn Gould’s Bach renditions left a marked impression on this writer as a 17-year-old student of composition.

At the start of our lessons, I was offered a refresher course in melody and counter-point (the two most important components in any song). Bach’s fugues and preludes were a perfect subject of study for me at this time, and Jeff introduced me to Glenn Gould’s masterful renditions of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier—which completely revolutionized my understanding of a song’s potential. He then encouraged me to bring in whatever songs I happened to be listening to at the time (mostly early Jackson Browne and pre-Yellow Brick Road Elton John), and we would break these down into individual moving parts. It was then that the dots began connecting for me, and my desire to create compositions of my own took a firm hold. My earliest compositions were nothing more than experiments in counter-point: without abiding by any pre-determined time signature, I would improvise one melody against a simple counter-melody, and then challenge myself to map it out on a grid. (Several years later, I stumbled upon David Byrne’s writings on music and composition, which taught me non-traditional ways to map out songs on paper—without having to stick within the parameters of those dreaded lines on sheet music. These have most definitely been a useful reference point throughout my songwriting experiments.)

Even though my scheduled sessions with Jeff ended well over a decade ago, I consider myself a student for life. As I continue composing, producing, and engineering recordings with Dirty/Clean, I find myself learning from other individuals involved in this process every step of the way. The mixing process can be an especially challenging and overwhelming part of recording, and I’m fortunate to have had the invaluable assistance of Derl Robbins (The Keynote Speaker, Motel Beds, The Company Man) on both of the Dirty/Clean records. Some other great teachers I’ve found over the years are those masters of composition and record-making: George Martin; Bob Johnston; Tony Visconti; Brian Eno; David Bowie; John Cale; Neil Young; Mark Mothersbaugh; Giorgio Moroder; Quincy Jones; Nile Rodgers; Conny Plank… There is so much to be gleaned from the works of past masters, and record collecting/listening is one of the most effective ways (as far as I’m aware) of cutting to the chase. And thanks to the advents of YouTube and Wikipedia, it’s now easier than ever for fledgling musicians to study our history of recorded music—not just through the songs themselves, but through the countless documentaries and tutorials archived in these video streaming libraries.

“…get into the car…”

Seven years ago (or so), I chanced upon an ’80s tribute show at a venue called Canal Street Tavern, which used to be located at the corner of First and Patterson in downtown Dayton. I commended some of the performers after the show, and spoke with a drummer, Jay, who seemed to be filling in for every band on the bill that night. We spoke about some of our mutual musical interests, and I mentioned that I was a keyboard player. After several further meetings, a mutual decision was made to endeavor playing music as a duo, and thus began our quest for a sound we could both agree upon. We joked about how ideal it was to have only two band members (“it’s the least number of additional people you need to be called a band”), but we eventually made our live debut as a 6-piece—in a Duran Duran tribute show, nonetheless.

Following this experimental outing, the 4 friends who joined us on-stage that night moved on to their respective projects. We shifted the focus back to making something work as a duo, and ventured out on several DJing forays. The most thoughtful of these efforts was a weekly exercise in combining live performance with music cues, which served to help prepare us for some of the challenges inherent to having only two players. It was around this time I discovered the films of Fassbinder, and this opened a concentrated portal into several subjects of on-going interest for me (namely: self-oppression, gender politics, family formation, and systems of control). I was especially taken at the time with Fassbinder’s made-for-television mini-series, Welt am Draht (World on a Wire). As I was struggling to come to grips with the ways in which social media was changing interactions with peers, friends, and acquaintances, the subject matter of the film seemed to speak directly to my struggles. The concept of trying to reconcile multiple virtual realities at once, frame upon frame, was no strange concept to me: it’s the way I felt every time I corresponded with acquaintances over the internet, then met a completely different side of the individual in-person. Beyond inter-personal anxieties, there was my somewhat more profound fear of human cognition being altered (perhaps permanently?) by the luxury of immediately accessible information.

Official music video for “Fall Things”—a tribute to the film work of Godfrey Reggio and Stan Brakhage.

Around this same time (2012, or so), the discovery of Scott Walker completely re-shaped my outlook on the frontier of popular music. I discerned some abstract connection between the divergent soundscapes of Walker’s varied incarnations, and the movement known to many westerners as “krautrock”—which had followed on the heels of a markedly bad gulch of German MOR (then referred to as “schlager musik”). Just as bands ranging from Can to Neu!, to Kraftwerk and Cluster had reshaped the future of all music (and seemingly from scratch), Scott’s peerless venturing into unknown musical territory presented a similar hope in the promise of mystery and mastery. The connection between Scott and “neue musik” was further established in my mind upon the discovery of Fassbinder’s Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant, in which an LP record of Walker Brothers recordings plays a vital (if minor) role in the unraveling of its characters.

Margit Carstensen puts on a Walker Brothers record in Fassbinder’s The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant © 1972, Criterion Collection

As a duo, Dirty/Clean continues to function as an exchange of (frequently disparate) influences between myself and Jay: some of these influences overlap in our respective libraries; others remain permanent outliers. One source of mutual inspiration has always been disco (which, in turn, links back to my obsession with neue musik). While Jay’s knowledge of disco far exceeds my more dabbling interest, we share a profound appreciation for the functional quality of the genre. It is the ultimate music to move to, really: the pace tends towards the pace of one’s heart (if doing some kind of aerobic activity), and the fixed nature of the rhythm once lent itself to several years of seemingly endless—and surprisingly unique—variations. Of course, disco has had a fair share of harsh criticism heaped upon it throughout the years (not unlike surrealism): it’s been called repetitive, boring, MOR slop; it’s even been referred to as fascistic. But we’ve both recognized a different angle to this music. We’ve recognized music that has the power to unite; music with a pulse. Music that can range in content from utmost sincerity to utmost banality, and yield a successful result at either end of the spectrum.

I like to think of myself as a fairly eclectic listener, but like most people, I tend to fall in line with a particular strand of influence—and then spend a substantial amount of time lost in that strand. We’ve just recorded a follow-up album to Welt am Draht, and the motorik beat seems to continue propelling us along. I sometimes doubt the songwriting ethics of retaining a given beat so consistently, but I usually come around to my pre-existing mantra: “if it works, it works.” I cannot say with any degree of certainty where we will be heading next in this musical co-operative. I only hope to continue exploring unknown territories (at least, unknown to us).

“…we’ll be the passenger…”

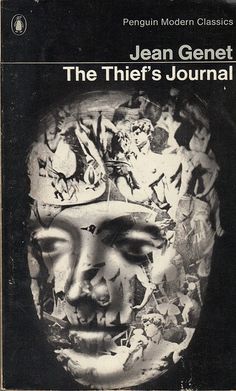

For me, the journey of making ulter nation ends with Jean Genet. “Saint” Genet’s writings have been a fixed reference point in my creative efforts over the past few years: it is his understanding of the power of gestures that continues to empower my modest efforts. Edmund White’s comprehensive biography of Genet, more-so than any other source on the subject, seems to capture the sweeping gesture that was Genet’s life—whose very origins were colored by his own attempts to mislead biographers, historians, and the reading public in general. Genet is the most rewarding read of my life thus far, and I recommend it to anyone with the stamina for 700 pages of fine print (it flies by: honest).

The Thief’s Journal by Jean Genet, first published by Gallimard in 1949

It could be argued that every age is an age of gestures. I would argue that the digital age is the most dangerous of all—in that it allows individuals the illusion of performing an action, when that action is often nothing but a digital fingerprint. As surveillance and fear of government intrusion colors our everyday activities, it is significant to note the steady dilution of our gestures; the gradual and perilous reduction of truly fearless gesturing—which used to be the defining feature of a life lived to its fullest.

Our nation is entering a confusing new chapter; a chapter wherein many long-standing forces of oppression remain unchanged, and yet the strategies once used to counter them have seemingly become obsolete. Absolute corruption has won out at the highest level of government, and it is important for all caring individuals to recognize that simple gestures of empathy may now be the most subversive gestures of all. Just as Genet realized in writing The Thief’s Journal, “traditional” acts of subversion and violation are part and parcel of a society that has been eroded from the top down:

“I’d wanted to steal. A strange force held me back. Germany inspired all Europe with terror, it had become, especially in my eyes, the symbol of cruelty. It was already outside the law. Even on the Under den Linden I felt I was strolling through a camp organized by bandits. I believed that the brain of even the most scrupulous Berliner harboured treasures of duplicity, hate, nastiness, cruelty, greed. I was struck by being free amidst an entire people listed on the index. Surely I would have stolen there, but I felt disturbed, since what triggered this activity and what resulted from it—the special moral attitude erected as a civic virtue—a whole nation understood and used against others.

‘It’s a nation of thieves,’ I felt within myself. ‘If I steal here I will not be performing a singular action that can better realize my nature: I’ll be obeying the normal order of things. I won’t be destroying it. I’ll commit no evil, I’ll disturb nothing. Scandal is impossible. I’ll steal in a void.’”

We are left having to reconsider our options for effectively confronting and dismantling a system that insists on imposing oppression, while acting out crimes far worse than the perceived transgressions of the oppressed. We are left having to identify alternatives for this state of institutionalized corruption (which can be equated to that old Caligari-esque saying, “the inmates are running the asylum”). We must dream of an ulterior nation to the one we are entrapped by, and we must preserve the strength to carry this dream to fruition. We must resist the urge to steal in a void, and instead, turn away from the void altogether—towards the spaces that surround it; those unknown buildings that await our occupancy.

And so, I continue riding through the city’s back-sides, searching for an open door into this ulter nation. I continue accruing cultural interest—expanding my potential for empathy, and striving to balance these creative pursuits with the personal responsibilities of work and home life. And I ride, and I ride…

“…singing la, la, la, la, la-la-la-la…”

* * *

ulter nation is available for digital download and CD mail order on the official Dirty/Clean BandCamp page.

Album artwork by Roger Owsley © 2016

Some footnotes:

1Ironically, the closest a film has come to capturing my memory of the Italian films shown on television while I was growing up is Down By Law—an American-made independent film by Jim Jarmusch, starring Roberto Benigni and real-life spouse, Nicoletta Braschi, in a pair of roles that intentionally echo the roles they’ve played in numerous Italian comedies.

2Beyond Buñuel, there are the lovely films of Jean Cocteau and the experiments of Man Ray. Also, the spectacular films of Jean Vigo and Jean Painlevé, which are only slightly removed from the surrealist movement.

5It is interesting for this writer to note that, while Placebo are celebrating their 20th anniversary with a worldwide tour, they are selling out arenas in Russia and Germany; they have not booked any dates in the United States.