“We are the United States of Amnesia: we learn nothing because we remember nothing.”

With these words, Gore Vidal summarized (albeit somewhat cynically) what seems to be a recurring motif of our country’s ancestry. And it does stand to test that we, as a nation of people, have persistently struggled to effectively process our past. Like a patient who keeps returning to his therapist for analysis, but then disregards the insight provided about himself during every session, we seem to carry on in a state of oblivion—forever wondering what on earth might be the matter with this dysfunctional country we live in, when the answers have been presented to us time and time again…

The great Tilda Swinton, playing a mother who fears her child might be developing sociopathic tendencies in Lynne Ramsay’s adaptation of We Need To Talk About Kevin © 2011, Oscilloscope Pictures

In Lionel Shriver’s acclaimed novel, We Need To Talk About Kevin (later developed into a chilling film by Lynne Ramsay), the author explores the psychology of a family whose parents struggle to come to terms with their child’s emerging sociopathic tendencies. Ignoring the author’s advice, Kevin’s parents fail to adequately explore what might be the matter with their increasingly disturbed son, and (spoiler) unnecessary bloodshed ensues. The text functions as an apt dramatization of a real-life struggle within many American families—namely, the disregard of clinically established mental health issues, which all-too-frequently debilitate (and sometimes destroy) otherwise functional family units when ignored and left untreated. But it also functions as a pointed criticism of our country itself: a country that has the highest death rate by gun violence among all the developed countries in the world (as cited in a 2010 report published by The American Journal of Medicine), yet refuses to acknowledge the benefits of common sense gun control; a country that was founded upon, arguably, the most egregious of all documented acts of genocide in world history (as summarized in great detail by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz in her text, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States—among many others), and yet continues to minimize the egregiousness of these crimes against humanity (read this thoughtful yet infuriating piece by Guenter Lewy, who appears to be gunning for title of “hair-splitter extraordinaire” in his justification of these crimes); a country that—after having wiped out the native peoples of said country—proceeded to import slaves from other countries around the world to do our dirty work, while our ancestors feigned religious superiority; a country that, once forced to grudgingly acknowledge the heinous and un-Christian acts of slavery it perpetuated and legislated, slowly proceeded to modify the institutionalized oppression of people of color into forms of segregation—and later, into the Machiavellian mass incarceration of minorities, whose byproduct (or intention, depending on how one dissects the situation) has been gross profiteering at the expense of an unpaid labor force in for-profit prisons (“a rose by any other name…”).

And the list goes on; and the denial goes on; and the oppression goes on. This isn’t to say that our history isn’t being properly re-evaluated by present-day historians, documentarians, and artists; but it does much to substantiate Mr. Vidal’s argument. Consumed by the notion of progress, but ignorant to the painstaking effort and integrity required to truly achieve progress, we’ve by and large mastered the art of the dog and pony routine: instead of subsidizing adequate efforts to alleviate gross income inequality, house the millions who are homeless, and ensure basic healthcare and education for our tax-paying citizens, we’ve committed ourselves to “liberating” the denizens of countries abroad. And bear in mind, this is not an attempt to oversimplify the accepted complexity of diplomatic relations with foreign nations: we do (at least, for the time being) retain a Constitutional freedom of speech that many men and women across the oceans from us are bereft of. But since we are entering an era where “telling it like it is” is valued over respecting nuance and the ever-resented gray areas of our running history, I suppose it’s only proper that I should follow suit(?)

Then again, is that not the root of our problem? For how can we tell anything like it is, if we refuse to properly investigate what “it” actually is, or has been? If we persist in filtering the failures of our nation’s forefathers through a lens of “Manifest Destiny,” via which just about any crime (including ethnic cleansing) can be rationalized under this pathetically childish euphemism for “finders keepers”? As prone as we are to distilling the gray into black and white, I have an unshakable conviction of the urgent task at hand: to accept and to paint the gray areas we are so often inclined to ignore, and to talk—to actually talk, and listen when spoken to—about our past in terms that are frank, clear, and evidence-based. It’s not an easy task, by any means, but I can provide examples for reference as to how one might proceed.

* * *

In April of 1945, British forces liberated the last of the still-living prisoners discovered in Bergen-Belsen and Neuengamme—the last of the Nazi concentration camps to fall to the victory of the Allied Forces. During the years that ensued, the people of Germany faced a unique conundrum: while their economy rebounded at an extraordinary rate (so extraordinary that it was referred to at the time as an “economic miracle”), the citizens of this troubled nation struggled to incorporate the reality of their recent past into the greater scheme of their national history. Many accounts I’ve read by then-living German citizens argue that the years following the war were marked by quiet denial; by an unspoken refusal to address the proverbial elephant in the room, and later, by several political regimes of dubious merit (let us recall that, a mere 16 years later, a great wall was erected between the two halves of this troubled country).

A snapshot of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, located in what is now Lower Saxony. Courtesy of the Holocaust Education & Research Team website.

And yet, if we fast-forward to the fall of the Berlin wall and the period of reunification that ensued, we will find a change has taken place. In 1991, an art competition is held in West Berlin to commemorate the Holocaust in the form of a national monument; the winning artist rejects the most popular idea—a central monument in the Bavarian Quarter—and chooses something far more affecting. From the hundreds of rules imposed by the Nazi regime upon the Jewish population in West Berlin, the artist selects 80, to be reprinted one by one on street signs throughout the Bavarian Quarter; so that, while waiting to cross the street, a passerby might stumble upon a phrase like “Jews aren’t allowed to leave home after 8PM,” or “Jews must forfeit all electrical devices”—reminders of an unforgettable atrocity, to ensure this atrocity will not be forgotten (and, with any hope, not be repeated). Mind you, this change did not happen overnight: this change happened gradually, over the course of half a century, and through the concerted efforts of artists and historians to come to terms (without justification or rationalization) with the full extent of their country’s history of genocide and oppression.

Fassbinder challenges his (real-life and screen) mother’s interpretation of German history, in his episode for the collaborative 1978 film project, Germany in Autumn, renewed © 2010, FACETS distribution.

It is because of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, Alexander Kluge, Volker Schlöndorff; Alfred Döblin, Otto Dix, Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder, Douglas Sirk; Karlheinz Stockhausen, Conny Plank, Michael Rother, Hans-Joachim Roedelius, and Dieter Moebius (among many others—too many to name in one essay) that this change took place. Because of Alfred Döblin and Otto Dix, the oppression brewing beneath the decadent veneer of the Weimar era was painted in broad relief—through the jarringly prescient words of the former, and the harrowing brushstrokes of the latter. Because of Fritz Lang, Douglas Sirk, and Billy Wilder, the hatred and genocidal racism prevailing in Nazi Germany was documented, satirized, and captured in real time through the medium of popular film (they did their jobs so well, they were all three forced to flee the oppression of the Nazi regime, so they could continue documenting and satirizing from a distance). Because of Fassbinder, the prejudice and amnesia that had become ingrained within his parents’ generation was dragged into broad daylight and brought to the attention of those who previously refused to pay attention. Because of Conny Plank, Rother, Roedelius, Moebius, and all the pioneers of the neue German musik, the foundations of a better future were laid within the cultural narrative—wiping the slate clean of all the MOR “schlager” detritus, and offering an alternative to the sins of their fathers through entirely new art forms. And to this day, Wim Wenders continues carrying the torch for the country of his namesake, painting some of the most beautiful moving pictures man has ever known—reminding viewers around the world of just how precious and significant these little lives of ours are, and giving us cause to carry on loving and learning more about each other.

Which brings us back to the U.S. of A.—a country that, as Meryl Streep so pointedly remarked during her headline-making acceptance speech at the Golden Globes this past Sunday, has become so eager to reject immigrants that it might soon have “nothing to watch but football and mixed martial arts, which are not the arts” (and I suspect that, despite the slightly sarcastic undertone of that little caveat, there are many who would beg to differ with her chagrin at this notion). Without meaning to come across as pessimistic or overly self-deprecating, I can and will readily admit the painful truth: that we are a nation drowning in our own ignorance. We have forgotten how to love one another, because we have forgotten how to foster a loving society. We have invested so much in our institutions of religion and our splintered ideologies, and in doing so, we have forgotten the simple gestures that reveal love in its truest forms.

Roger Ebert famously referred to the cinema as a “a machine that generates empathy,” and yet a substantial chunk of the top 100 grossing films of 2016 (and 2015, and 2014, and 2013…) consists of obscenely violent action blockbusters which do nothing to generate empathy, and actually function through a reversing of this very formula: they are the products of a machine that aims to belittle and eradicate empathy. To be perfectly fair—and with respect to those gray areas I’m endeavoring to highlight—there were many films in this year’s top 100 that stand up to the litmus test of Ebert’s definition; in fact, the #1 box office success of the year, Finding Dory, is a populist but shining example of empathically-geared family filmmaking. And yet, the age demographic that seems most in need of empathic development—namely, the voting age demographic—doesn’t seem to be picking up on the message. We have to scroll down to the 70th percentile of the top box office grossers before we find a film (Fences) that addresses the ever-growing racial divide in our country; we have to scroll to the 80th percentile before we find Manchester By the Sea, one of the most remarkably skilled and affecting pieces of American film realism this past year (at least when it comes to fostering empathy for characters on-screen, and for the struggles they contend with). And we won’t even find the most powerful machine for empathy to tour the film circuit in 2016 (Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight) among the top 100 box office grossers this year; I can only hypothesize that the appeals of Jack Reacher: Never Go Back and The Legend of Tarzan were too irresistible to sacrifice in favor of something that might serve to edify and enlighten. (For comparison: Ken Loach’s latest documentary, I, Daniel Blake—a study in the failure of the British welfare system to adequately provide for the needs of an ailing carpenter and his family—can be found in the top 100 grossing films of both the British and French box offices. Can you imagine?)

Ken Loach’s latest documentary film, one of the highest-grossing pictures of the year in England and France © 2016, Sixteen Films.

But the task at hand involves more than just empathy-building (which ought to be a given in any civilized society): we need to pair our empathic skills with our critical thinking skills, and difficult as it might be, we need to wean ourselves off of this addiction to sanitizing history—of our passion for distilling all those varying shades of gray into crisply delineated shapes of black and white. I can already see (and am myself contending with) the struggle ahead, as we prepare to wave so long and farewell to our current commander-in-chief: a man who rather gracefully served as leader of this country for the past 8 years—all the while speaking in complete sentences, refraining from extramarital affairs in the Oval Office, and polishing that veneer of social progressivism that we liberals cling to so readily. Difficult though it might be, I believe it is crucial that we not forget the unfulfilled promises of this seemingly squeaky clean administration. The failure to close Guantanamo Bay, as promised; the implementation of drone-bombings in the never-ending war for oil in the Middle East; the growing socio-economic divide among the citizens of this country; the endless flow of the almighty dollar between lobbyists, Congressmen, and the Executive branch—influencing nearly every decision that is made at every level of Federal government.

Let’s not do what the Republicans did with Reagan in the ’80s, and the Democrats did with the Kennedys in the 60’s: let’s not turn the work of a flawed man into a gilded legacy act, impermeable to the critique and reasoned analysis of future generations. Let’s celebrate the fact that we finally elected a person of color to the highest office in the country, but let’s also acknowledge and respect the limitations of his work—just as we must acknowledge the institutionalized racism that continues to prevail throughout so many structures of our haphazard economy. Let’s bear in mind that, should we live to tell the tale of our 45th president, there are likely to be individuals who persist in championing the infallibility of his being; and who are we to cast stones, if we cannot refrain from making the same mistake in lionizing our current president’s time in office? It is only by cutting our losses now that we will be able to adequately number the (possibly innumerable, I fear) losses we’re preparing to sustain throughout the next four years.

So at long last: can we begin to talk about Us? Can we drag ourselves, as a nation of people, to the analyst’s chair that is the study of history, and can we truly examine the ghosts lurking within? It’s an unpleasant task, and I understand the general reluctance to undertake it, but I trust we have the means and the resources to do so. It will require self-awareness and discipline, to be sure; it will require taking the time and effort to engage in open dialogue with individuals who cling to a conviction that differs from ours. Instead of shaking our heads at the seemingly uninformed statements of younger people—so often coated in a language that seems to betray an over-developed sensitivity—we must seize upon each and every opportunity to inform and educate: we must respect (and strive to learn from) their views of this confusing world they’re growing up in—and whenever appropriate, we should offer an expansion to their perspective (which might also serve to alleviate that heightened urge to mind every single “p” and “q” spoken in public).

Lastly, we must rediscover the significance of the arts in our daily lives. Although I don’t foresee the United States maturing enough to rein in its fanaticism for gladiatorial sports, I believe we have the capacity to meet halfway by restoring the arts to a place of heightened importance in our schools; I believe we have the capacity to invest in our country’s fledgling artists way more than we currently do—not just by subsidizing the works of up-and-coming artists through government sponsorship (let us bear in mind: nearly all of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 30-odd films were publicly funded by the German government), but by making a deliberate effort to seek out works that endeavor to comment on and elucidate our present and our past. We simply cannot continue referring to ourselves as the Greatest Nation on Earth, when our state of cultural affairs remains in such vacuous disarray.

Mr. Vidal was easily one of the greatest satirists ever to emerge from our country, and his passing has left a notable void in the satirical department. We need intellectuals to continue seeking out new, innovative ways to engage the minds of our nation’s youth—as well as stimulating the dormant thought processes of so many a working adult. It was because of Vidal’s incisive commentary that so many of us took the extra time to investigate the folly of our country’s forefathers, and it will be because of similarly capable analysts that we might manage to do the same moving forward. Because I still retain a (quite possibly foolish) belief in the far-off possibility of guiding the dilapidated, runaway train that is the United States onto a track of reason, reflection, and true progress—and I believe I am not alone.

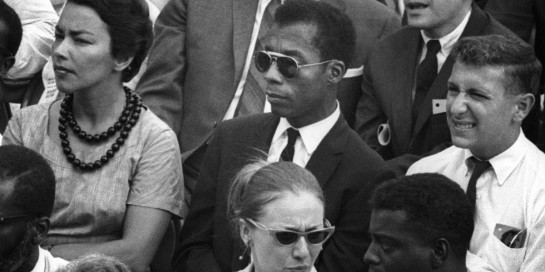

Still taken for the forthcoming Raoul Peck documentary, inspired by the words of James Baldwin © 2017, Velvet Film.

But first, we must take the time to recall—and to challenge our recollections, when we fear they may have faltered. In our efforts to restore reason and empathy to this fallen land, we must invest as much energy as the artists of the German new wave invested in studying and repairing their own history. Documentaries such as OJ: Made in America, 13th, and the forthcoming James Baldwin film, I Am Not Your Negro, are an important step in this direction—but I’m convinced we can do so much more (especially when it comes to supporting these efforts with actual numbers). Whenever we watch a movie, read a book, or look at any piece of art, we should be asking ourselves and each other: what is this telling me about myself and my fellow man? Does this message ring true?

And what have I learned?

“If no one asks, then no one answers

That’s how every empire falls.”

– John Prine