“Everybody looks so ill at ease

So distrustful, so displeased

Running down the table

I see a borderline

Like a barbed wire fence

Strung tight, strung tense

Prickling with pretense

A borderline”

So sang Joni Mitchell in one of her finest and most incisive songs—”Borderline,” from her early ’90s (quasi-)masterpiece, Turbulent Indigo. In a subsequent verse, the artist paints a vivid portrait of those who “praise barbarity / in this illusory place / this scared, hard-edged rat-race.” In closing, she gracefully dismisses the futility of every ideology mapped throughout the song, stating casually and assuredly that: “All you deface, all you defend / Is just a borderline.”

While there are many songs in the Joni canon that can repeatedly bring me to my knees or force me to eat crow, “Borderline” presents a rather singular fait accompli. Because the entirety of human ideology crumbles under the weight of this simple yet elegant text; including every indulgence in such borderline surveillance, which Yours Truly has ever been myopic enough to commit to writing.

I can no longer number on the fingers of my two hands, the number of times in recent history that I’ve repeated a particular platitude: “we are living in strange times.” Every time I repeat the phrase, I seem to betray a quasi-mystical hope—hope that some rational explanation for our circumstances might be drawn from the ether of such banal truisms. Perhaps the time has come for us to throw in the towel, in searching for any explanation to any of this madness. Or perhaps, it is necessary for us to re-engage the power of the mind, and step outside the now-driven-into-the-ground parameters defining our socio-cultural dialogue. To examine this battleground from a different perspective altogether; to question the very validity of our failed parameters, and try—for a change—to actually understand where we are (vs. insisting on getting to where we want to be, as quickly as possible).

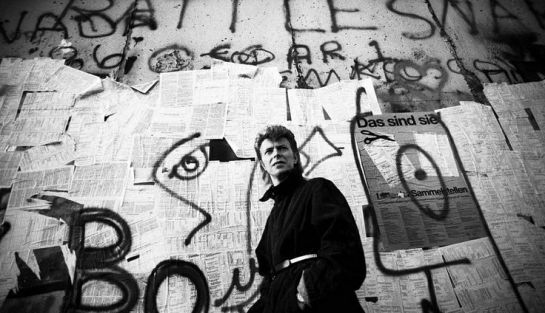

David Bowie, standing by the Wall in Berlin; circa 1987, Glass Spider Tour. On the day after his passing, the German Foreign Office responded to the news by thanking him for helping to bring the wall down.

In my most recent post, I reflected upon the on-going relevance of David Bowie’s penultimate studio album, The Next Day. The post was titled after the album’s surprising lead single, “Where Are We Now”—in which the artist reflects upon his days spent living in West Berlin, during the late 1970s, recording a trilogy of monumentally influential albums with Brian Eno and Tony Visconti (as well as producing and co-writing a pair of equally significant Iggy Pop solo albums). The visually startling music video produced to accompany this single, directed by installation artist Tony Oursler, presents a static portrait of the artist’s studio life during this time: “sitting in the Dschungel;” “walking the dead,” waiting for a train. Though I’ll admit to being mildly perplexed by the song (and its choice for lead single) at the time of its original release, I can hardly think of a more timely artistic expression of what it feels like to live in 45’s America. The feeling of being frozen in time—unable to move forward or back; waiting at a terminal for a train that may never arrive, but unwilling to step outside the station for fear of the horrors that surround you on all sides (not unlike the oppressive weight of the Berlin Wall—yet another futile borderline).

In such a climate, reflecting on the past will continue to prove a necessary task for planting the seeds to a better future. For there remain clues scattered throughout our history, which may well provide us with the guidance needed to prevent this uncertain future from becoming an endless, Nietzschean reiteration of our pre-apocalyptic present.

* * *

I was struck with the inspiration to pen this entry, after reading a noteworthy academic journal by Ringo Ossewaarde (a professor of sociology at the University of Twente, in the Netherlands). I stumbled upon the piece while searching for writings on dialectical reasoning in the 21st century, and I advise the reader to set aside the time needed to digest in its entirety. If you only have time to read one long think piece today, please close out of this post and give Mr. Ossewaarde precedence; for while I may not personally deem some of the ideological fears he ruminates on quite as severe as he deems them to be (and while others, like the resurgence of fascism, seem more pertinent to our present-day situation), I’ve rarely read a piece of philosophical inquisitiveness as pointed, engaging, and nuanced as this one.

In struggling to make sense of the messy political conditions we presently find ourselves in, it dawned on me that a lot of the conversations taking place among us on the national front seem to suffer from an abuse of classical debate models. Rather than originating from a place of reason, observation, and friendly dispute, most of our conversations on contemporary subjects seem to originate from a position of deliberate antagonism. An eristic position, as opposed to a truth-seeking position. With antagonism as the norm, it ought to come as no surprise, when individuals who have adopted a truth-seeking outlook are misunderstood by their detractors, and (unsurprisingly) taken down a notch for daring to seek the most truthful common thread—as opposed to indulging in the more lucrative activity of professional hair-splitting. Ossewaarde captures this emergent dichotomy with great aptitude and precision:

“In Plato’s The Sophist (226a), Socrates identifies the Sophists with ‘the money making species’, thereby asserting that they do not dispute for the sake of the search for truth but instead engage in the dispute as professionals, to articulate their own truth claims for a reward or as a job. In other words, the dialectic turns eristic when friends come to depend (for their rewards) on their own truth claims, so that they become unwilling to negate their initial views (negation would make them lose their rewards). Since victory and not truth is the ultimate goal of the eristic discussion, the Sophists rarely change direction and hence are incapable of progressing towards truth.”

And with one paragraph, Ossewaarde successfully outlines the disease that prevents us, as a society, from making any progress towards alleviating the animosity of our conversation. And while specific changes in policy (such as the Reagan administration’s overturning of the FCC’s Fairness Doctrine; which effectively opened the doors for our ratings-and-sensationalism-driven news networks, and their rosters of theatrically impassioned talking heads who make a fortune by not bending to reason) have no doubt exacerbated our situation, it seems our culture—as well as the cultures of many European ancestors—have been drifting further away from truth-driven dialectical reasoning for decades prior to such official policy changes.

Raphael’s painting of the School of Athens, located in the Vatican, it portrays the commingling of sophists and philosophers in a polis setting.

And while Ossewaarde’s journal singles out the dominant ideology of popular liberalism as one of the most toxic and limiting ideologies currently in vogue, one could double down on the same charges as they relate to neo-conservatism (beginning with the Nixonian era of American politics). Thus, the greater significance of this journal seems, to me, a broader awareness that “ideology is a disease of the mind.” A statement which, bold as it may seem, I find myself hesitant to counter. For have we not seen the rise and downfall of nearly every ideology known to man? And have we not witnessed the devastating effects such trends seem to have on the development of the human consciousness? From cults to religions; from feudalism to colonialism; from communism to fascism. Arguably, socialism provides the only notable exception to this rather overarching rule. And one could argue that this is due to socialism itself being rooted in liberalism—still an overriding force in global culture, precisely because it is the most rational of all the “ism”s currently on the table.

To clarify: Ossewaarde’s critique of popular liberalism (which incorporates multiple insights from thinkers like Mannheim and Mills) is not, explicitly, a critique of the founding principles upon which liberalism has been built. Rather, his critique aims to clarify how popular liberalism has managed to take noble concepts and distort them in such a way that has actually proven detrimental to their advancement. Take, for instance, three ideas central to the liberal ethos: civil rights, gun control, and public services (health, education, and unemployment benefits, for instance). On all three issues, liberals generally hold a more rational stance than their conservative counterparts—though fortunately, some conservatives seem to be shifting towards the light. But if one were to accept Ossewaarde’s critique of liberalism (as a positivist ideology), one would have to acknowledge that we might’ve found a better way to convey the truthfulness of the liberal position; at least, something above the blowhard tactics of a Chris Matthews or a Bernie Sanders.

Similarly, this critique holds up when one considers the splintering of liberals into increasingly small subsections: the pitting of one puritanical ideologue against another, perceived-to-be-less-than; resulting in a climate wherein a liberal feminist (HRC) who had engaged in some misguided commentary (much of it having been prepared by male advisors surrounding her) and used an insecure email server, could be deemed—by some—a greater threat to progressive talking points than a populist demagogue with a mafioso predisposition, actively espousing anti-progressive rhetoric, and willingly adding fuel to a raging fire of xenophobic sentiment. Whereas one individual may see the forest for the trees, another may only see the branches that don’t align with their personal vision of the forest. And it is this very failure to reconcile reality as-is, with one’s personal interpretation of how reality ought to be, that results in the “mind that can no longer think well” (Ossewaarde, p. 408). (Just as this writer still finds himself struggling, on occasion, with the reality that 45 is still the President of this country, despite every indicator that he oughtn’t be at this time; and despite every bone in my body recoiling at every idiotic gesture of his idiotic and actively oppressive regime. There have been times, no doubt, that this mind has not been able to think well about all this; which, to some conspiracy theorists, could be deemed another objective of this administration’s strategy to divide, conquer, and deflect attention away from the puppet-masters.)

In turn, Ossewaarde succeeds in dismantling the most popular utopian “distortion” of reality perpetuated throughout the annals of sociological philosophy. Marxism is therefore seen as: “an eristic (read: an argument that aims to successfully dispute another’s argument, rather than searching for truth) pathology to dialectical sociology… Not only does Marxism make an illegitimate use of the dialectical method, but, in that use, it theorizes the historically determined transcendence of the contradiction in an historically fixated end state – the classless society.” It is, like all other utopias, a fantasy that cannot and will never be achieved; because the dialectic it seeks to suppress is, in this writer’s humble opinion at least, inherent to human nature itself.

Oprah Winfrey hosts a roundtable reunion of panelists who were first interviewed eight months into 45’s term as president. © 2018, CBS News.

For evidence of the dialectical urge in human nature, one need look no further than the number of U.S. voters who have lent their full support to the most mentally unstable president we may have ever entertained (or been shamefully entertained by). In televised interviews with some of the voters in question—including a recent Oprah panel reunion on 60 Minutes—one finds that these individuals are not, as is often portrayed by voices on the left, explicitly bigoted lunatics who wouldn’t know a book if it hit them in the face (though, to be certain, they exist also). Rather, they seem to be predominantly marked by a quality of anti-liberalism; which is different than anti-intellectualism (though occasionally commingled), because its antagonism lies most heavily within the notion of a truth being thrust upon them with no identifiable choice—versus being engaged in a rational dialogue that might enable independent acknowledgement of evidence supporting the correctness of liberal views (which, admittedly, some people will refuse to acknowledge even after a Socratic tutorial). Sometimes, this desire for active engagement manifests itself intentionally (i.e. “I can’t get past the way liberals talk”), other times, with little to no awareness of this desire even existing. In viewing the above-mentioned 60 Minutes piece, one may well note that the liberal-leaning panelists in this segment rarely succeed in effectively conveying the objective facts supporting their views. Rather, their attempts to relay the righteousness of their perspective is more commonly rooted in an observable emotion, which (to someone who might not share in the emotion, having not yet grasped the information which provoked it) generally serves to cloud the objective merit of the information being conveyed.

At the close of Ossewaarde’s thought-provoking commentary, the writer asserts that the greatest hope for a more radical sociology lies in the pursuit of a modern-day Socratic polis (publics)—sans slavery, of course—”in which the paideia – high culture – is continued through radical sociology.” This requires a separation from the elitist (and racist) mindset that underwrote the Greek polis, and an active process of adaptation to the circumstances of 21st century life within society. Most essentially, such an ideal can only be met if, and when, radical sociology succeeds in implanting itself within the machine of global capitalism. As explained by Michael Burawoy (a public sociologist who is currently attempting to reconcile an interdisciplinary range of sciences with capitalist enterprise): “globalization is wreaking havoc with sociology’s basic unit of analyses – the nation-state – while compelling deparochialization of our discipline.”

In other words, having altered the basic unit upon which the study of sociology was established, the pursuit of a globalized industrial complex (and its residual, globalized culture effect) has enabled powers on both the left and the right to call into question the very usefulness of a dialectical sociology (while, curiously, they still refuse to join forces in a single party of globalized fascism; for this is what modern life would resembled, if stripped entirely of dialectical thought. The debate perseveres; which means that some thought remains, however distorted it may have become). An inverse dilemma is raised from this rejection of the dialectic: for if sociology has provided the backbone to social progress over the past millennia, can social progress stand a chance, when sociology is removed from its original role in the conversation? (And where might the arts, as we know and love them, find a more relevant place in this conversation?)

Burawoy and, to a lesser extent, Ossewaarde both seem cautiously optimistic about our chances for transcending the “ism”s of our time. Ossewaarde writes: “Since the positivist sociologies no longer serve the victorious, radical sociologists should no longer aim at negating positivism (Burawoy 2005a: 261, 266). Liberalism is no longer the foe of radical sociology. In the current crises of global capitalism, the very possibility of Burawoy’s public sociology and its resistance to global capitalism depends on a co-operative partnership with the positivist sociologies. This partnership is not a dialogue or friendly dispute between sociologists or scientists in general. Instead, it is a new deal in which positivism provides sociology with the legitimacy of a scientific discipline, while public sociology makes sociological knowledge accessible to democratic citizens, enabling them to make public issues out of their private troubles [emph. added].”

This may not seem like utopia to the reader, but it may well be the most comparable experience we can realistically hope for.

* * *

Where is hope?

While you’re wondering what went wrong?

Why give me light and then this dark without a dawn?

Show your face!

Help me understand!

What is the reason for your heavy hand?

Was it the sins of my youth?

What have I done to you?

That you make everything I dread and everything I fear

Come true?

Following the heavy blow of “Borderline” and the softer darkness of “Yvette in English,” Joni’s Turbulent Indigo closes with her magisterial “The Sire of Sorrow (Job’s Sad Song)”—in which the singer boldly re-appropriates the narrative of Job from the perspective of a woman (which, one supposes, is no more bold a gesture than that time she re-appropriated Yeats’s “Second Coming,” for her marvelous and profoundly underrated Night Ride Home album). It is a song—and a record—for our times; with its aching plea for an end to the never-ending reaches of trauma, and its desperate yearning for some hopeful resolve. Juxtaposed against the radical sociology of Ossewaarde and Burawoy, Joni’s music provides the inevitable counterweight to pure objectivity: pains for which no cold, objectively delivered explanation will suffice; horrors which no reasoned debate can rescind. The pure subjectivity of human trauma and lived experience, seeking resiliency through artistic acumen.

As I write this entry, I find myself simultaneously reading about the role that Facebook has played in the escalation of an ethnic cleansing underway in Rohingya, Myanmar. A report on the findings of a recent UN study, exploring the factors that have contributed to this genocide, indicates that: ” [Facebook] has … substantively contributed to the level of acrimony and dissension and conflict, if you will, within the public. Hate speech is certainly, of course, a part of that. As far as the Myanmar situation is concerned, social media is Facebook, and Facebook is social media.” I recall the immediate aftershocks of 45’s election and subsequent inauguration; aftershocks which included a spike in U.S. hate crime, as well as the broadening revelation that Russian-funded social media propaganda had played a significant role in furthering homegrown acrimony. I think of how all these factors might’ve played out differently, had our culture not drifted so far afield from dialectical reasoning. Had radical sociologists played a more significant role in the evolution of social media technology, or had Ted Nelson been successful in launching his alternative proposal to the World Wide Web model (Project Xanadu). It is alarming, saddening, and somewhat humbling to see how a single century of human history can yield so many shortsighted turns; giving way to a chain reaction of negative consequences—some predicted, many unforeseen—and leading us to our present circumstances.

Ted Nelson, interviewed in the 2016 Werner Herzog documentary on the history of the internet, Lo and Behold: Reveries of the Connected World. © 2016, Magnolia Pictures.

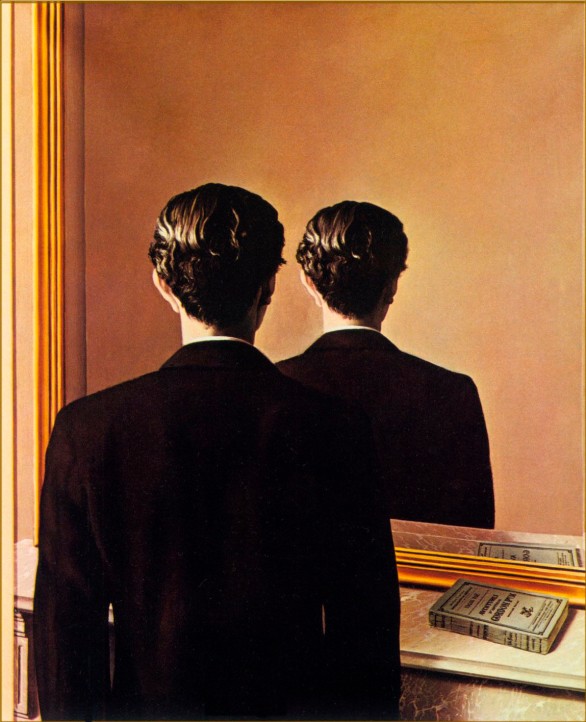

I cannot seem to erase this longing, at the very core of my being, to (in New Testament fashion) turn over the tables in the marketplace of our status quo, and insist upon a return to some form of reasonable containment for dialectical contradictions. And while I am reluctant to overestimate the possibilities for art bringing about such a revolutionary change, I continue to be inspired by the surrealist ethos: to create such a shock to the nervous system of the established order, that it cannot help but question the sustainability of its own terms. As art continues being co-opted by the contemporary positivist movement, which seems intent on reforming the arts in an a priori manner (so as to make them redundant), perhaps that counter-reaction to the institutionalization of bourgeois sensibility—once referred to as the nouvelle vague—may have its day in court, once more.

For it is not a question of whether the dialectic will be recovered, or whether humankind will awaken to the benefits of its implementation in society. The dialectic is. If we do not take the necessary steps to accommodate its existence within the fabric of our reality, it will simply continue rearing its stubborn head in ways that further destabilize and undo the best laid plans of mice and men. Might we make room for it, instead?