Studying Salò

“As to the future, listen:

its fascist sons

will sail

toward the worlds of the New Prehistory

I’ll be there

like one dreaming of his own damnation,

at the edge of the sea

in which life begins again.

Alone, or almost, on the ancient shore

among the remains of ancient civilizations.

Ravenna

Ostia, or Bombay—it’s all the same—

with Gods picking their scabs of old problems

—such as class struggle—

which

dissolve . . .

Like a partisan

dead before May 1945,

I will slowly decompose

in the tormenting light of that sea,

a forgotten poet and citizen.”

—from the Pasolini poem, “A Desparate Vitality”

It would be prudent at this point to make some mention of the past—of the Marquis de Sade and the literary origins of Salò. What I would like to attempt here is a reconciliation between the lives of Sade and Pasolini, and this behemoth of eighteenth century literature yoking them together; for just as The 120 Days of Sodom was Sade’s first major work, and the cornerstone upon which the rest of his writings are based, so it provided the subject of Pasolini’s final masterpiece and (for better or worse) the work he will be most commonly remembered for. The challenge of this effort is to maintain the respective logic of these two artists alongside any relevant analogic pertaining to their correlation. I find it far too easy to blur the lines, to allow oneself the luxury of rendering everything hazy for the sake of vague association. But neither Sade nor Pasolini took the easy way out in any of their undertakings, and they deserve a similar commitment to faithful exploration. So let us begin where it all started.

Christened Donatien-Alphonse-François de Sade on June 3rd, 1740, the Divine Marquis was plagued by contradictions from the very start—because the name originally intended for him was Louis-Aldonse-Donatien, and the one bestowed upon him was a mere misinterpretation (this misnomer would cause him numerous headaches throughout his life, particularly during the period of the First French Republic). His first run-in with the authorities took place on Easter Sunday of 1768, following an acrimonious encounter with an out-of-work cotton spinner whose sexual services he had employed. After ordering her to undress, he reportedly threatened her with a knife and proceeded to flog her; one might say it was all downhill from there for Sade. Perhaps the greatest irony of Sade’s existence is that, for all his wickedly virile imagination, the “crimes of love” committed during his lifetime were quite petty: in addition to the Easter incident, he served some spiked candies to a few prostitutes and engaged in sodomy with his manservant. Critically acclaimed musicians have gotten away with far worse. But the crimes for which Sade paid most dearly were his intellectual crimes—his atheism, the explicit sexuality of his writing, and his unwillingness to comply with bureaucratic regulation. Beyond the mildness of his misconduct, the Marquis actually behaved quite ethically throughout his life. His greatest gripe over the years would be with his mother-in-law (the letters addressed to her from his period of incarceration should be required reading for anyone contemplating marriage), but it was his wife to whom he addressed this eloquent confession of benevolence:

“I am a libertine, but I am neither a criminal nor a murderer, and since I am compelled to set my apology next to my vindication, I shall therefore say that it might well be possible that those who condemn me as unjustly as I have been might themselves be unable to offset their infamies by good works as clearly established as those I can contrast to my errors. I am a libertine, but three families residing in your area have for five years lived off my charity, and I have saved them from the farthest depths of poverty. I am a libertine, but I have saved a deserter from death, a deserter abandoned by his entire regiment and by his colonel. I am a libertine, but at Evry, with your whole family looking on, I saved a child—at the risk of my life—who was on the verge of being crushed beneath the wheels of a runaway horse-drawn cart, by snatching the child from beneath it. I am a libertine, but I have never compromised my wife’s health.”

I find it important for anyone interested in studying Salò to appreciate the contradictions that defined Sade’s reality: not only do they show through in The 120 Days of Sodom, they provide the very core of Pasolini’s film. How else does one explain the fact that his protagonists are actually the embodiment of everything he despised, or his struggle to downplay the naked beauty of young men on account of his recent shift in ideology? As I will attempt to demonstrate in the following pages, Pasolini’s turmoil had more than a little in common with the Divine Marquis’s, and it is rather fitting that his final completed effort should forever unite him to Sade in a film that, with any degree of hope, will never cease to be infamous. With that preface out of the way, it is now time to take a closer look at the text behind Salò.

Sade’s novel is possibly the most austere atheistic fiction ever penned. Never before, or since, has a book been so joyously profane, so celebratory in its rejection of god. Although Justine may be his best read—the most entertaining of his rails against virtue—The 120 Days of Sodom cannot be topped for absolute extremity and strength of determination. With Salò, Pasolini goes beyond atheism: he not only defies the notion of a loving and sovereign creator, he defies the notion of human sovereignty—which Sade himself defied, but in a somewhat more contradictory fashion (in that Sade actually found comfort, pleasure, and a perverse form of sovereignty in man’s capacity to act against the principles of nature). There is no true pleasure in Pasolini’s depiction of twentieth-century consumerism, and that variation between his own perspective and Sade’s makes all the difference, philosophically speaking: whereas Sade built an entirely hedonistic worldview out of his desire to subvert virtue and religion, Pasolini’s exposition of a godless, virtue-less society is one he finds terribly unsatisfactory. His approach to filming Sade might be akin to a father wishing to withhold some unfortunate reality of the world’s workings from his son, but not wanting to deceive either, he proceeds to explain the injustice of humanity in full.

The injustice presented in Salò is both moral and religious, but there is a highly political framework as well, and it presents a further paradox when Sade’s beliefs are taken into consideration. For Sade, the most sickening and perverse notion of all—worse than virtue and piety, even—was capital punishment. Torture and perversion being, in his eyes, the instruments of a libertine, they are to be pursued exclusively in the name of private (preferably intellectual) pleasure and/or vengeance; the greatest subversion of this ethic imaginable would be the anonymous, public ruling of an individual’s guilt or innocence, as well as any subsequent punishment administered by a third party. It was not so much the injustice that Sade abhorred, as it was the lack of personal involvement: how could a judge possibly obtain pleasure out of a sentence, the execution of which is not his to perform, and the rhetoric being couched in hearsay and an implausible objectivity? Such an act is a betrayal of man’s capacity to behave in accordance with a carefully deliberated subjectivity, hence a betrayal of Sade’s dogma.

Upon close scrutiny of the libertines in Sade’s novel, one might notice something askew here: that is, all four of them are (or had once been) authoritative figures—a financier, a bishop, a Duc, and a president. Moreover, the president (Curval) reveals that he had once been a member of parliament, and “must have voted at least a hundred times to have some poor devil hanged; they were all innocent, you know, and I would never indulge in that little injustice without experiencing, deep within me, a most voluptuous titillation.” What ever happened to that scorn for capital punishment, one might ask? The deliberate contrast between the individual philosophy of Sade, and the fictionalized philosophy of his characters, is crucial, and it will be for Pasolini as well. Students of Sade’s, such as Pierre Klossowski (whose essay, “Nature as Destructive Principle,” is referenced in the bibliography of Salò, to be discussed later), often made the mistake of attributing the words of his characters to Sade’s own belief system, but this is a dangerous misstep—as noted by Simone de Beauvoir in the brilliant, if heavily Freudian, essay, “Must We Burn Sade?” The significance of The 120 Days of Sodom as an atheistic manuscript is that, with this writing, Sade aimed (and succeeded) to expose the distinct possibility for an anarchic society, governed by rules no less strict–in fact, far stricter—than those present in a moral society. It was not as significant for Sade’s characters to be faithful incarnations of his own ideology, as it was for them to represent the very antithesis of goodness and virtue, thus underlining the absurdity of faith in a god and/or moral code so easily susceptible to reorientation. Consequentially, what we have in The 120 Days of Sodom is not a direct representation of Sade’s fantasies, but merely the elaboration of a society wherein his own preferred “crimes” would be only a drop in the bucket of absolute corruption.

Now, let us consider the role of the four fascists portrayed in Salò: they are the extreme incarnations of Sade’s libertines, and the acts of violence authorized by them throughout the film are, essentially, the rulings of a political entity. They consistently uphold the rules and regulations drafted in the opening scenes as the reasoning behind their actions, not unlike a judge justifying his ruling via some legal precedent or other; on the way to the villa, they even delegate an order to shoot an escaped victim, rather than performing the deed themselves. The libertines in Sade’s novel obsessively devise a corrupt web of ritual whereby they can wantonly carry out their personal passions; in Salò, their fascist counterparts devise rituals whereby they might become the ultimate incarnation of power. Which begs the question: how does one separate the concept of self-serving regulation from that of corrupt public bureaucracy? Can corruption for the sake of corruption ever exist, or is there always a personal interest at stake?

Fast forward 200 hundred years from Sade: it is 1974; not only have the secular writings of Marx, Stirner, Nietzsche, and Foucault been published worldwide, their theories have already been (mis)interpreted and put into action through the convoluted forms of Nazism-Fascism, Stalinism, and Maoism. I cannot help but draw an abstract comparison here between the manner in which Marx’s Communist Manifesto was perverted by Stalin and Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra warped by Hitler, and the method employed by Pasolini to willfully manipulate the writings of Sade. Let it be clear that I am in no way attempting to compare the heinous crimes of history’s most renowned genocidal maniacs with the artistic efforts of one of the twentieth century’s great poets and thinkers—rather, I find it noteworthy that the distortion of theoretical concepts in service of megalomania is not only referenced in the content of Salò (and all throughout the writings of Pasolini, for that matter), but echoed in its very form. Bear in mind that Pasolini was himself an outcast in the political arena: excommunicated from the Italian Communist party as a direct consequence of his sexual predilections, he could not have become any more disenchanted with the popular realization of theories he still faithfully subscribed to—especially in light of the rising middle class and its doctrine of consumerism. In “The Power Without a Face: the True Fascism and therefore the True Antifascism,” Pasolini sizes up the situation with achingly pointed foresight:

“The identikit of this new faceless Power vaguely assigns to it certain ‘modern’ traits derived from tolerance and from a hedonistic ideology perfectly autonomous. But this identikit also assigns to this power ferocious and substantially repressive traits; the trait of tolerance is in fact false, because in reality there is no man who is supposed to be so normal and so conformist as the consumer, and, as for the hedonistic ideology, it clearly hides a decision to prearrange everything with a ruthlessness as yet unknown in history. Therefore, this new Power, not yet represented by anyone and caused by a ‘mutation’ of the ruling class, is in reality—if we really want to keep the old terminology—a ‘total’ form of fascism.”

While I believe it is Godard who most explicitly and relentlessly documented the effects of consumerism on European society throughout the second half of the twentieth century (2 or 3 Things I Know About Her is probably the most singular cinematic document of this nature), no film is as affecting and visceral in its condemnation of fast-food culture as Salò. Perhaps this is because the world developing around Pasolini was so alien to him, so offensively incompatible with his own views, that the expression of his disgust could not possibly be as restrained as Godard’s more subtly subversive approach. But this violently thoughtful passion, which I find painfully absent in present-day film-making (it remains active in other facets of the art community, particularly performance art), is precisely what makes the film such an overwhelmingly vital experience.

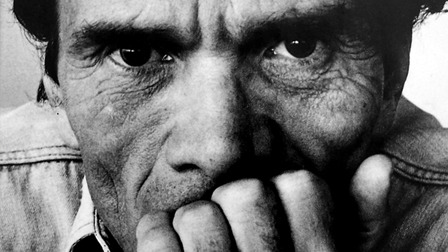

Consider what, for Pasolini, was beautiful about mankind: the regional dialects of Italy’s diversified social structure; the almost primitive quality of street hustlers; the wrinkled, weathered faces of farmers whose lives revolved around water, soil, and the changing of the seasons. In essence, the nobleness of simplicity—the non-competitive power of individual consciousness (as opposed to the failed attempts of social consciousness, which only contributed to his own exile). This provides the most direct of any link to Sade, whose struggle was the epitome of an individual against a collective. For Sade, and for pre-Salò Pasolini, individual sovereignty was the most significant, and significantly overlooked, of all worldly concepts. As elucidated by de Beauvoir in “Must We Burn Sade?:”

“If the entire population of the earth were present to each individual in its full reality, no collective action would be possible, and the air would become unbreathable (sic) for everyone. Thousands of individuals are suffering and dying vainly and unjustly at every moment, and this does not affect us. If it did, our existence would be impossible. Sade’s merit lies not only in his having proclaimed aloud what everyone admits with shame to himself, but in the fact that he did not simply resign himself. He chose cruelty rather than indifference … In the solitude of his prison cells, Sade lived through an ethical darkness similar to the intellectual night in which Descartes shrouded himself. He emerged with no revelations but at least he disputed all the easy answers. If ever we hope to transcend the separateness of individuals, we may do so only on condition that we be aware of its existence.”

If one were to attempt a reconciliation of these perceptive observations with the pervasive ideologies of 2013 … well, one might as well not attempt such a feat. As predicted by Godard and Pasolini, consumerism and conformism have successfully devoured the final diversified dregs of society, and the current emphasis on “saving the middle class” is shining evidence that their forewarnings fell upon deaf ears (which presently appear far too hypnotized to endeavor reorientation). Guided by a misappropriated sense of “knowing,” most of today’s educated elite appear utterly oblivious to the inevitable facts of heterogeneity. Indeed, the only humanistic efforts which have reaped a (sometimes faint) beneficial outcome have been those targeted at correcting an imbalance which society has put in place itself (i.e. the legally sanctioned discrimination of individuals based upon sex, race, age, sexual orientation, etc…); any efforts targeted at the correction of an imbalance which is innate to society (such as the inescapable dynamics of social stratification) have not only failed time and again, they have served to further distort the notion of individual sovereignty. There are few developments over the last fifty years more appalling than attempts, both public and private, to ostracize materialistic poverty (in imitation, a form of eugenics) and impose product placement upon civilizations whose existence had gone on for centuries without their alleged aid. As people across the globe blindly accept flat-screen TV’s, laptops, smartphones, electric nose hair trimmers, and revolving trends as symbols of their livelihood—and actually look down upon anyone who might deem some of these novelties superfluous—the fate of mankind is sealed as prophesied by Philip K. Dick and Isaac Asimov: one silicon chip at a time.

If I am giving the impression here that Pasolini was some sort of utopian idealist, or, as is more commonly perceived, an obstinate intellectual who refused to participate in any group activity that didn’t correspond 100% with his own ideology, then I am not doing him justice (which I could never hope to achieve in full, but am obliged nevertheless to avoid misrepresentation to the best of my ability). It was not Pasolini who rejected the Italian Communist Party, nor was he responsible for the unsubstantial manner in which his portrayals of erotica were being mimicked at the time of his death; although too intelligent and self-realized to become a “victim” in the traditional sense of the word, he was thoughtlessly maligned by the very people he made such pained efforts to reach an understanding with. As stated in his final interview: “…everyone is weak, because everyone’s a victim. And everyone’s guilty, because everyone’s ready to play the murderous game of possession.” Like Sade, his greatest crime was being sincere enough to acknowledge the convoluted nature of man, a crime responsible for the death he described in “A Desperate Vitality”—the one that “lies not in being unable to communicate, but in the failure to continue being understood.”

Having to stand alone comes across most plainly in Pasolini’s writings as his greatest fear, but it is the other side of this coin which he defines as the real tragedy: the misguided hopes of those standing together on hollow ground. His final writings are replete with a genuine concern for society that is a far cry from the cynical reputation unjustly awarded him. These last, unremitting pleas to be understood are heartbreaking, both in their earnestness and their exactitude. When he writes of his readiness to have his own principles diluted, in a last-ditch effort to be heard in the political arena, one cannot help but cringe at the sense of urgency; just read “What is This Coup? I Know,” written a year prior to his murder, if you have any doubt about this. But as conformism became increasingly widespread, as nuanced points of view were carefully weeded out and replaced by miserably watered-down rhetoric, there was no longer room for Pasolini anywhere in the public sphere. These were the circumstances under which his final published interview was conducted, the one he presciently suggested be titled, “Because, we are all in danger.” I have read and re-read the interview on numerous occasions, and each time I am struck by the sheer density of its integrity, along with its disquieting prophecy. The response that lingers most forcefully in my mind might be the following (when asked to clarify his nostalgia for “Brecht’s beautiful world”):

“My nostalgia is for those poor and real people who struggled to defeat the landlord without becoming that landlord. Since they were excluded from everything, they remained uncolonized. I’m afraid of those Black revolutionaries who are the same as their landlords, equally criminal, who want everything at any cost. This gloomy ostentation toward total violence makes it hard to distinguish to which ‘side’ one belongs. Whoever might be taken to an emergency ward close to death is probably more interested in what the doctors have to tell him about his chances of living than what the police might have to say about the mechanism of the crime. Be assured that I’m neither condemning intentions nor am I interested in the chain of cause and effect: them first, him first, or who’s the primary guilty party. I think we’ve defined what you called ‘the situation.’ It’s like it rains in the city and the gutters are backed up. The water rises, but the water’s innocent, it’s rainwater. It has neither the fury of sea nor the rage of river current. But, for some reason, it rises instead of falling. It’s the same water of so many adolescent poems and of the cutesy songs like ‘Singing in the Rain.’ But it rises and it drowns you. If that’s where we are, I say let’s not waste time placing nametags here and there. Let’s see then how we can unplug this tub before we all drown.”

I turned on the television the other night and just flipped through the (allegedly) different channels, something I haven’t done in many years: I saw a cartoon bear telling me how to wipe my ass and what brand of toilet tissue to wipe it with; a grotesque woman yelling crassly at a group of child dancers; several action-driven investigative serials, each one totally indistinguishable from the next; people yelling on a news program, all of them desperate to have their feelings heard, none of them offering even a semblance of intellectual insight; a “reality show” in which four ridiculous-looking “judges” are seated on even more ridiculous-looking thrones, and a tarted-up child is offering them an over-emotional interpretation of some agonizingly harmless pop song; stand-up comedians—lots of stand-up-comedians—none of them funny; more people yelling. Water everywhere, and not a drop to drink. If there were some way, any way to unplug this tub, I would be near the front of the line to pull the cord. So many people already appear to have drowned, flooded by today’s equivalent of “adolescent poems and cutesy songs,” inundated by an ignorance that is innocent only insofar as it believes itself to be insightful. Even the voices of contemporary dissidents like Noam Chomsky and Jello Biafra are fading from earshot, squeezed out by reality show contestants vying for their fifteen seconds of fame. I’ve seen the future—brother, it is murder.

This is why Pasolini turned his back on those young and beautiful bodies—those mischievously poetic faces (recalling Rimbaud) that were the very substance of his prior inspiration. Not only had consumerism successfully inundated the once-pristine countryside with plastic bottles and prophylactics, but via the mainstreaming of pornography, the beauty and purity of eroticism he strove to capture in his Trilogy of Life had been obtusely turned against him in the form of sleazy knock-offs such as The Lusty Wives of Canterbury and The Last Decameron: Adultery in 7 Easy Lessons. There now remained nothing the powers that be were unwilling to make a profit from, and this realization must be in part responsible for Pasolini’s subsequent choice of Nazism-Fascism as plot device—for what better example of hollow profiteering is there to be found in world history?

The acts committed during the Holocaust are not altogether unique when one considers the countless instances of genocide throughout the course of time. What separates Nazism-Fascism from, say, Apartheid—or even Stalinistic communism—is the extent and sheer magnitude of its organization. Never has a government mechanism been put to such brutally calculated use, particularly not in the name of a “greater cause” (in this instance, the cause being eugenics). And that idiosyncrasy is precisely what Pasolini engages to tinker with Sade’s original intent in The 120 Days of Sodom. His characters are not acting upon personal feelings and attitudes against religion, as is customary for a proper libertine, but rather upon a notion of anarchy as the ultimate philosophy of power. They are the final remnants of a genocidal machine in the process of collapsing, bent upon spending their dying breaths exercising anarchic free will. Pasolini is in no way sanctioning the individualistically anarchic philosophy of Sade: he is revealing this philosophy as a monstrous fact of life, the ramifications of which Sade himself possibly failed to acknowledge (though his writings indicate an acute awareness of mankind’s capacity for destruction, his degree of speculation is difficult to gauge). And here, one finds yet another blurred line of demarcation between Sade and Pasolini.

Sade found solace in parody, his format of choice since popular poetry of the late 1700’s was, by and large, quite conservative (and, for lack of a better word, flaccid) in its parameters. Webster defines “parody” as: “1: a literary or musical work in which the style of an author or work is closely imitated for comic effect or ridicule 2: a feeble or ridiculous imitation.” In the case of Sade, the style being ridiculed is of a behavioral, as opposed to literary, nature—which is true of most great parody: Sade consistently mocks the conduct of ordinary men (often of a bourgeois persuasion), juxtaposing it against the hypothesized perversion of his libertines. The parody of Sade is also riddled with comedy, albeit of a rather dark variety; in The 120 Days of Sodom, for instance, his libertines are in a constant state of inebriation, a state which is frequently exploited for crude comic effect. During one particular passage, a libertine is attempting to read aloud the regulations in effect for punishments about to be administered their victims, but is too drunk to follow words on the page. This sort of humor does not serve effectively as amusement, but it does serve to reveal the offhandedness of Sade’s cruelty; never do we get the sense that Sade finds anything particularly brutal in his descriptions—if anything, he seems to have pondered every possible permutation of cruelty to the point of becoming bored with it.

Pasolini, on the other hand, found solace in poetry; but for what would become his final film, the shape taken was of both parodic and tragic proportions. Webster defines “tragedy” as: “1 a: a medieval narrative poem or tale typically describing the downfall of a great man, b: a serious drama typically describing a conflict between the protagonist and a superior force (or destiny) and having a sorrowful or disastrous conclusion that excites pity or terror, c: the literary genre of tragic dramas, 2 : a disastrous event.” At a glance, there does not appear to be any conflict between the protagonists in Salò (the four fascists) and any superior force, but that is because Pasolini has turned this arcane formula on its side; in Salò, the terror results from the fact that no superior force succeeds in interfering—or even attempts to interfere—with the protagonists’ cruel intentions. The inevitability of every atrocity perpetuated throughout the film (which could easily have borne the words, “A disastrous event.”, as its tagline) is what the viewer finds most discomforting, along with the merciless repetition of said atrocities.

Then there is the tragedy that Pasolini defined in that final interview, the tragedy of modern man: “What is the tragedy? It’s that there are no longer any human beings; there are only some strange machines that bump up against each other … Wouldn’t it be wonderful if, while we’re here talking, someone in the basement were making plans to kill us? It’s easy, it’s simple, and it’s the resistance.” To this day, it is unknown whether or not Pasolini’s death was the product of conspiracy. Eight years ago, new evidence was uncovered, and the individual who previously claimed responsibility for the murder retracted his confession; Pasolini’s long-time friend and collaborator, Sergio Citti, testified that some of the film rolls for Salò had been stolen, and at the time of his death, Pasolini was on his way to meet the alleged thieves. But the evidence was deemed inconclusive, and the case promptly returned to the archives of unsolved homicide.

Salò is indeed a funereal ordeal, as screenwriter Pupi Avati insists in an interview conducted for the 2008 Criterion re-release; but it is also a vicious parody. The film provides graphic mockery of consumer culture in a variety of forms, ranging from the purely literal to the wholly symbolic. Oftentimes, it occupies both forms simultaneously. The notorious scenes featuring coprophilia can be interpreted to represent the abstract notion of man reduced to a pre-rational state through his addiction to junk products; it is also relevant today in a literal sense, as the fact that fast food products contain traces of fecal matter has become general knowledge. Another example of this multi-faceted parody can be found in the burlesque wedding ceremony of the third act, which I am inclined to interpret as a depiction of what Pasolini termed the “decision of consumerist power to grant a tolerance as vast as it is false.” This particular observation bears even greater relevance in 2013, as gay marriage is becoming gradually acknowledged by governments around the globe. I sometimes wonder what Pasolini would make of these attempts to sanction the very thing which cost him his right to political involvement: would he be celebratory, as so many gay and lesbian individuals are today? After all, this is a major step in the direction of establishing legal equality for gays and lesbians. Though it is impossible to say for sure what his altogether singular thought process might make of these sanctions, I think it safe to say that he would greet them somewhat warily. After all, it is already evident to most long-time supporters of gay marriage that the popularity of this issue did not arise from a sudden, genuine shift in popular opinion, but rather from political parties becoming aware of the issue’s viability as a carrot-stick to lure the voting bodies. Once it becomes a given for both conservatives and liberals to endorse gay marriage, the novelty will have worn off, and the general population will be left to face its true, repressed feelings towards a diversity of sexual preferences (something most people are unwilling to admit their discomfort for, preferring to mask unease with a false tolerance).

As I mentioned previously, the accusation of “contradictory” could easily be leveled against Pasolini (and frequently has been), but it must be pointed out that seldom has a voice been so consistent in its contradictions. After all, if it were not for this consistency, his testimony would not remain so frustratingly engaging—a statement which could easily be transposed to Sade. And if one spends a significant amount of time with Pasolini’s writing, one might notice that what at first glance appears to be contradiction is actually the product of logic so far beyond ego-centred rationale, it requires a total reevaluation of social indoctrination in order to begin wrapping one’s mind around it—yet another uncommon achievement we can attribute equally to both authors. What I do find wholly distinctive between the two is the relationship of the ego to their respective philosophies: Sade, in part as a consequence of the religious superstition dominating the time in which he lived, wrote persuasively about the omnipotence of the individual ego, thus lighting a path for his readers to follow in lieu of hollow church dogma; Pasolini, in a day and age dominated by rising atheism and materialism, would feign a somewhat more egoless approach to unite the intellect with the soul. Both, through general ignorance and misinterpretation, wound up having their all-too-noble efforts swept beneath the proverbial carpet.

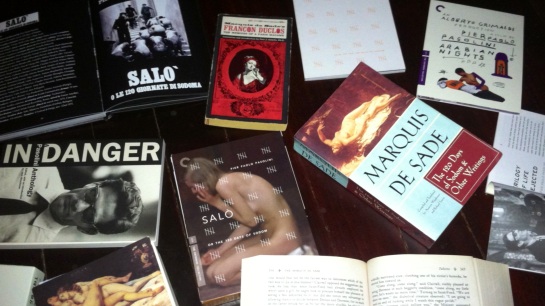

Salò remains the only fiction film I have ever seen to be introduced by a bibliography of suggested reading. More than being directly referenced in the film, this bibliography serves to place Salò in a literary context: Pasolini wanted the public to understand from the first just how distant this production was from the sensuous eroticism of the Trilogy of Life. In fact, he went so far as to exclude Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom from said bibliography, further confounding his vested interest in the critical pursuit of Sade’s work. The only other fiction film I have seen to feature a bibliography was Von Trier’s Antichrist, in which the ending credits contain a list of related writings on the purportedly innate evil of the female sex. It is a relief that there remain provocative and thoughtful filmmakers such as Von Trier, even if his audience will most likely always be limited to cinephiles and sociopaths; but following the murder of Pasolini in 1975, there has not been a soul daring enough to carry his torch any further (the closest link might actually be musical: one-of-a-kind composer/singer/artist Scott Walker wrote an achingly beautiful tribute to Pasolini, “Farmer in the City,” for his 1995 album Tilt—and much of his work from that album onwards bears the thoughtful historicity which so distinctly marked Pasolini’s oeuvre).

And so the question remains: why is it that two of the greatest writers and intellectuals the world has ever known are also two of the most universally ignored? Taking this train of thought even further, why are they not mandatory teaching in universities? As I see it, the film of Salò is a veritable Pandora’s box, replete with essential history and philosophy; it could easily merit the study of an entire semester. But here the age-old question is bound to arise: can a work of art do harm? By teaching Sade, is it possible that some unstable student will misinterpret the subject matter and use it as inspiration for criminal activity? To these questions, I would say that any film, book, song, or painting—even (or especially) patriotic propaganda—is susceptible to misinterpretation, and this should not be grounds upon which to bar an extraordinary intellect from the classroom. The important thing is that the works be discussed and debated; it could even be argued that the ideology of Sade is only half as significant as the dialectic it inspires. Like a civilization that refuses to accept its most vital lessons, we are doomed to retread the same ground, making the same mistakes time and again, unless we try coming face to face with the past.

Yet, as pointed out by Maurice Blanchot, a large portion of the value attributed to Sade’s life and writings pertains to their scandalous reputation, and the fact that he has continued to scandalize for centuries beyond the grave is the ultimate testament to his achievement. Likewise, with Salò, Pasolini set out to create a work of art so extreme it could not possibly run the risk of commodification through peddlers of middle-of-the-road consumerism—and to this day, the film stands in a league of its own. Although there have been more graphically extreme movies since the time of its release (The Human Centipede, A Serbian Film, perhaps even Antichrist), not one of them offers a fraction of Salò’s radically intellectual merits. Pity: that one of the most incendiary philosophical documents ever produced within the medium of film should only be mimicked in its visual extremities. To be fair, tackling the ideas of a radical literary figurehead, with whom modern intelligentsia are still struggling to assimilate, is no simple task.

Jean Paulhan, in his thought-provoking piece “The Marquis and His Accomplice” (an analysis of Justine, which Sade disowned in a manner not unlike Pasolini with the Trilogy of Life), rather eloquently phrases the difficulty of elucidating the intricately simple ideology of Sade without referring the reader directly to its source: “Here it will be said to me, and very justly said, that the truth we are seeking is too inaccessible, and is as foreign to our language as to our understanding. So indeed it is, and it should be plain that, rather than express it, I am simply endeavoring, once having set aside a space for it to occupy, to encircle it, to surround it.”

This is a pursuit the twenty-first century is in dire need of, as the omnipotent hypnosis of internet activity further confounds man’s desire to have things easily defined and readily accessed. These days, everything requires a tag with a description, and a shelf on which to place it. There must be a space for mystery to exist undisturbed, otherwise our lives have no meaning; this was once the very foundation for religion. But beyond the need for mystery, there is another, more urgent need at hand, and that is the need to never stop questioning the manner in which we structure our society. At the very heart of writings left behind by Sade and Pasolini lies a burning desire to reevaluate, redefine, and reconstruct human civilization, but today there are few (if any) intellects brave enough to follow in their footsteps. In describing the value of Sade’s writing, Simone De Beauvoir isolated what it is we must take away from the study of his work, and this goes for Pasolini’s as well: “It forces us to re-examine thoroughly the basic problem which haunts our age in different forms: the true relation between man and man.”

A Note on Numerology

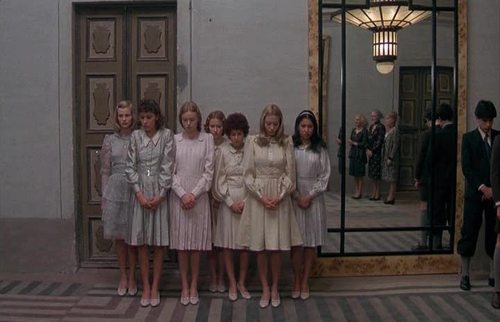

If one were to chronicle every significant discrepancy between Sade’s source text and Pasolini’s film bearing the same title (which I have attempted only in part; a thorough documentation could occupy entire volumes, and would eventually become pointless), one should make note of differences in numerology—the mathematics of Sade’s fiction being as central as its prose. In the source text, there are simply sixteen victims (eight male, eight female) to begin with. In Salò, the script begins with eighteen victims (nine male, nine female), but one of the boys is shot down by delegates near the start of the film (as mentioned previously), and soon after, one of the girls is found shot dead in a closet. Both events transpire within the first quarter of the film’s running time, and their shadow lingers powerfully over the remaining ninety minutes. I think it was a masterstroke on Pasolini’s part to start the film with a pair of arbitrary fatalities outside of Sade’s original sixteen victims; following those two sickeningly abrupt killings, the viewer endures the unrelenting harassment, torture, and abuse of the core cast as if it were a fate worse than death (which it is, as explained by the Bishop in a particularly chilling scene: “Fool, how could you believe I’d kill you? Don’t you know we’d want to kill you a thousand times to the limits of eternity, if eternity has any”). The young girl found dead in the closet provokes even further interest, since she closely resembles another of the principal victims, whose subsequent suffering we bear witness to as though it were the infernal punishment of her doppelganger—a possible link to the Dante device, which merits mention here as well.

Sade’s text is divided into four sections (or five, if one were to count the introduction), each section having been attributed a different narrator. Pasolini preserves this structure, then superimposes a structure from Dante’s Divine Comedy, condensing it to three sections (or four, counting the “Antechamber”) and assigning them each a different circle of hell. The overtness of this device can make it difficult for a viewer unfamiliar with the source text to appreciate just how brilliant it is; in effect, Pasolini has out-done Sade for precision, even altering related numerology in order to account for this alteration (as mentioned previously, Pasolini wrote eighteen victims into his screenplay, an even multiple of three—just as Sade’s sixteen was an even multiple of four). In the novel, the four sections break down as follows: “Simple Passions” narrated by Madame Duclos, “Complex Passions” narrated by Madame Champville, “Criminal Passions” narrated by Madame Martaine, and “Murderous Passions” narrated by Madame Desgranges. In Salò, the breakdown goes: “Circle of Obsessions,” narrated by Signora Vaccari, “Circle of Shit,” narrated by Signora Maggi, and “Circle of Blood,” narrated by Signora Castelli. Today, it is clear to historians that Sade was the true forefather of Freudian psychology, having catalogued thousands of sexual idiosyncrasies with maniacal precision. But I daresay Pasolini perfected the order of the inventory in The 120 Days of Sodom, establishing far more easily distinguishable categories for each set of passions. I cannot say this rearrangement merits widespread recognition throughout the psychoanalytic community, but it deserves to be noted that Pasolini and Sade both managed to synthesize their artistic efforts with a scientific sensibility—a truly remarkable accomplishment.